By Drew Hutchinson and Bailey Lewis

BONDURANT, Wyo. – Marlene “Lanie” Beebe stood in a pair of slippers, surrounded by scorched trees. A long gravel road led to rubble: shards of pottery, doll heads and a blackened metal chair. That’s where her neighbor, Nikki Cowley, said she found Beebe one day, among the remnants of 20 years in her home.

The next morning, Cowley saw Beebe, 74, at the end of the gravel road, hand-sifting through her shattered treasures. The ground was still on fire.

Beebe and Cowley’s homes were two of 55 residences in Hoback Ranches in western Wyoming that burned in the September 2018 Roosevelt Fire. Some homeowners were uninsured. None received individual financial help from the state or Federal Emergency Management Agency. Many have started rebuilding by hand.

“I don’t have anything left,” said Beebe, once a potter who had been living in her white Toyota Tacoma pickup.

FEMA provides two main types of disaster aid. Public assistance is used to restore public areas and buildings, and individual assistance gives financial help or services to people impacted by disasters in certain counties for things like housing and personal property.

But unless the incident is declared a major disaster by federal authorities, public and individual assistance aren’t available. Instead, FEMA recommended in a March 21 report, states should create and pay for their own individual assistance programs for disaster recovery.

Four states already have these programs. Wyoming isn’t one of them.

“I think (the state government realizes) we’re from Wyoming, and we’re going to make it happen with or without them,” Cowley said. “And I think it’s easier for them to just have us do it without them.”

Hoback Ranches is in Sublette County. An emergency declaration was not made because the disaster criteria weren’t met, said Jim Mitchell, the county’s emergency management coordinator. Wyoming’s governor at the time, Matt Mead, didn’t declare a state of emergency either, which means the county couldn’t be considered for FEMA aid.

Wyoming has a $500,000 disaster contingency fund, but it can only be used for “critical infrastructure” and only after a city or county makes a disaster declaration, said Kelly Ruiz, a spokeswoman for the state’s Department of Homeland Security.

States could do more to protect themselves and their citizens

Craig Fugate, the FEMA administrator under President Barack Obama, said states should take more responsibility.

“Some states do have programs and do provide assistance, but in general what many states have defaulted to is this idea that … if we don’t get to that threshold, we’re not going to create programs for (disaster assistance),” Fugate said.

Arkansas, Iowa, Ohio and Alaska have state-funded individual assistance programs to help fill gaps from the federal government.

After severe flooding in Crooked Creek, Alaska, in 2011, then-Gov. Sean Parnell activated the state’s individual assistance program because the flooding did not qualify for FEMA dollars, said Jeremy Zidek, a spokesman for Alaska’s Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management.

“The community had 14 homes destroyed,” Zidek said. “The federal government would look at that and say, ‘Well, the 14 homes are not sufficient to meet our individual-assistance thresholds.’ But the 14 homes were 14 of 40 homes within the community.”

Iowa’s program was created in 2010 for times when disasters don’t receive a major disaster declaration from FEMA, said Lucinda Parker, a spokeswoman for the state’s Homeland Security and Emergency Management department. People with incomes at or below twice the federal poverty line can receive up to $5,000 in reimbursements through the program, but only after the governor declares a state of emergency.

Both Arkansas’s and Ohio’s individual assistance programs fill the gap for losses not covered by insurance or other aid. Applicants have to apply to the SBA and be denied a loan before they’re eligible.

The burned sign to Hoback Ranches greets drivers when they turn off U.S. 191, and the once heavily forested, high desert terrain looms behind. Rim Road connects the area’s eastern and western parts, and Mountain View Drive winds into the ridges – now filled with tarnished aspen trees.

Hoback Ranches is a private, rural subdivision a few miles south of Bondurant, population about 100. More than 300 people and 100 species of wildlife share the area.

The Roosevelt Fire began Sept. 15 – the opening day of deer hunting season – near the head of the Hoback River, about 32 miles south of Jackson. The fire moved east over the next couple days, and Hoback Ranches was evacuated Sept. 18. By the time the fire was contained, 61,511 acres had burned.

How Hoback ranches esidents helped each other

Since the Roosevelt Fire, Hoback Ranches residents have relied on each other and surrounding communities. Many, Beebe and Cowley included, built their houses mostly by hand and are willing to do it again for themselves and others.

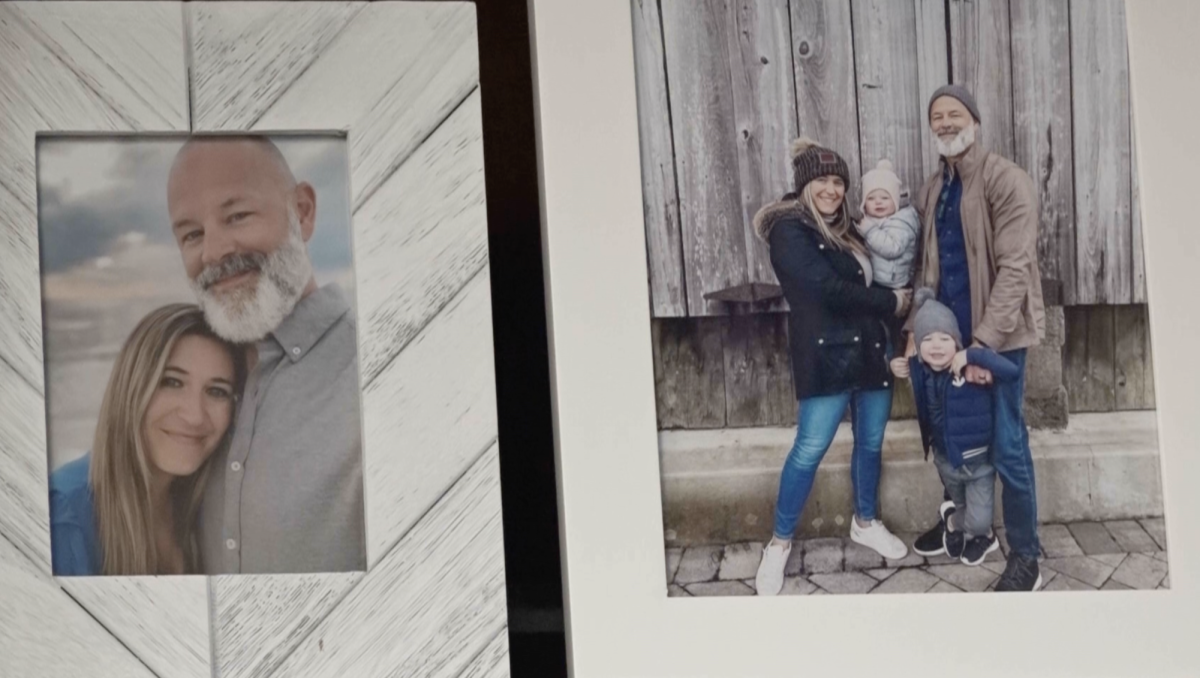

Cowley, a heavy equipment operator, said her main concern is Beebe, whose severe bipolar disorder has worsened since she lost everything.

Beebe made pottery professionally for 20 years before moving to Hoback Ranches. Boxes of her artwork and 20 years of journals filled her home and shed. It was gone in just 20 minutes.

“All that was left was one squirrel, one wheelbarrow, one kayak and 10 acres of charred timber,” Beebe said. “And so it was devastating. And I am still, of course, reeling from the effects.”

She continues to sift through the burn site in hopes of incorporating bits and pieces in new creations.

“So all of those things got trashed in the fire, but then, on the other hand, they could be – the broken pieces, the shards – could be resurrected and made into very interesting wall panels,” Beebe said. “And so the possibilities of that are endless.”

Andrea “Andie” Sramek, a former flight attendant and art teacher who moved to Hoback Ranches seven years ago, has been helping to look after Beebe. Sramek did not lose her home, thanks to a shift in the wind and a nearby lake.

“I was thankful, but then at the same time, I was devastated,” she said. “And I know it sounds bad, but they call it survivor’s guilt. And I’m ready for it to go away, but it hasn’t gone away.”

Sramek, who said she has multiple sclerosis, has organized countywide cleanup days, the most recent of which were in June. These cleanups are a chance for residents to get help sorting through rubble, disposing of debris and clearing charred trees.

Sramek said she invited Wyoming Gov. Mark Gordon to participate, but his spokesman, Michael Pearlman, told News21 that Gordon had scheduling conflicts.

“I had a lot of hope with our current governor, and now it’s disappointment,” Sramek said. “We need our leader, and he’s not there. Why?”

In fact, Sramek has been trying to get governmental help for Hoback Ranches since the fire. Mead, the former governor, visited the area in late October but never exited his car, Sramek said. Within a week, then governor-elect Gordon visited, spoke to residents and dined at Sramek’s house, saying he would try to help.

“I did come away with a sense that you are strong and will recover,” Gordon said in a Nov. 2 letter to Sramek. “You are all in my thoughts and prayers. Please take care.”

“Everybody matters,” she said. “But you know, you don’t feel like you matter when you’re forgotten about. And we’ve been forgotten about.”

The day of the fire, Cowley had just finished building her home with her husband. She had construction insurance but no homeowners insurance, which left her $300,000 underinsured.

“You go onto a site, and you don’t even know where to start,” Cowley said. “There is no checklist.”

She started the Roosevelt Fire Shed Fund, where she raffles guns to raise money to build sheds for those who lost their homes. Students from three local high schools, Big Piney, Pinedale and Jackson Hole, are helping build them. Beebe was the first Hoback Ranches resident to receive one.

“I’ve known (Beebe) for a long time, and she deals with mental illness, and she’s lost everything in her entire world,” Cowley said. “And her stuff wasn’t new. That was her mother’s or grandmother’s, her brother’s.”

Winter comes early and stays late in Wyoming, which makes the construction season short. Residents who are rebuilding by hand, like Cowley and George Bolcato, a five-year resident who also was uninsured, have a few months of good weather to construct a shelter.

With only the chimney of his home still standing, Bolcato is rebuilding using the unburned centers of charred logs. He works as often as he can on his property, Sky Mountain Ranch. During the night, he stays in Sramek’s guest room.

“You can’t buy that insurance policy that you missed,” Bolcato said. “The only thing you can do is look at what you have and go forward, and what I have is the land. So I decided I would build.”

Richard Thomas, a Vietnam veteran and 31-year Wyoming resident, is the Bondurant fire captain. He fought the fire for 13 days. He thought it could be contained, but the wind was ferocious.

By Sept. 23, called “Black Sunday” by residents, the fire had traveled more than 3 miles in 15 minutes to the middle of Hoback Ranches, Thomas said.

“Mother Nature decided it was going to burn, and there was nothing we could do to stop it,” he said.

Chuck Pfeiffer has lived in the central part of Hoback Ranches since 2015. His house was lost on Black Sunday. He was insured, but he’s chosen to rebuild by hand with his twin brother.

“We like to be able to say, you know, we did it all completely ourselves without additional hands whatsoever,” Pfeiffer said.

Pfeiffer spent 19 years in Florida, where he lived through several hurricanes. He never lost anything significant but still qualified for FEMA assistance once.

“So the difference is basically in Florida, it seemed like there was a lot more support for victims or people who went through hurricanes and so forth,” he said. “But you know, we just don’t have the number of people in (Hoback Ranches) to really get support or get any attention.”

To comply with the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act of 2013, FEMA clarified its requirements for individual assistance, which went into effect June 1.

“FEMA strongly believes states are ultimately responsible for the well-being of their citizens and that states have a responsibility to plan for disasters, pre-identify funding and resources, and to provide assistance to their citizens after a disaster,” FEMA wrote in the Federal Register report. “This should include the establishment, funding, and improvement of state-level individual assistance programs.”

But even states with individual assistance programs don’t cover damage to businesses – and neither does FEMA’s individual assistance program.

Laura Larson has lived in Utah her entire life and lost her business to flooding. She and her wife, Melissa, bought Camelot Resort in Fruitland in 2016.

The resort was untouched by the 2018 Dollar Ridge Fire, but two spells of heavy rain washed scorched earth, ash, sticks and other debris down the mountain and into the nearby river, which flooded shortly after.

“Never in a million years did we ever expect a fire to be the reason we flooded,” Larson said. “We didn’t think we needed (flood insurance) even though there was a river right through the middle of our property, and many of our neighbors were saying the same thing.”

After the second debris flow, which caused most of the damage, Larson realized it would likely keep happening until the vegetation grew back and stabilized the soil.

“So that was the moment where our hearts sank, and basically we were like, ‘OK, we’ve got to really think about something else,’” Larson said.

Utah, which had an estimated $1 billion budget surplus for the 2019 legislative session, has two disaster funds. But neither can be used for individuals or businesses, said Joseph Dougherty, the public information officer for Utah’s Division of Emergency Management.

One of the funds, created during the state’s last legislative session by Rep. Mike McKell, is for post-disaster response and mitigation efforts. McKell said creating an individual assistance program wasn’t part of the discussion, but that he’s open to suggestions.

Larson went to Duchesne County for help, and while they gave her a “good start” on cleaning up, the county did not have enough money to deal with all the damage, Larson said. She then contacted the governor’s office and other state officials, including Dougherty, and was told that no money was available.

“(Larson) has called me a couple of times just in tears like, ‘What am I supposed to do?’” Dougherty said. “And I’m like, ‘Unfortunately, if you don’t have flood insurance, then there’s nothing you can do.’”

Utah Gov. Gary Herbert declared a state of emergency in July 2018, but the fire never received a major disaster declaration, which Larson said could have helped her qualify for low-interest business loans from the state.

“It wasn’t like we were grossly mismanaging our business and then we lost our business,” Larson said. “This was something completely out of our control, and no one was there for us.”

Ultimately, Larson and her wife were forced to sell the resort.

“We’re good, honest, hard-working people,” Larson said. “Most of the world is good people working hard, and things beyond your control happen. It’s really unfortunate that the entity that could ultimately help is just not doing anything.”

Calvary Chapel St. George, a Bible church, bought the property and renamed it the “Promised Land Resort.”

News21 reporter Dustin Patar contributed to this report.

University of Oklahoma Seniors Drew Hutchinson and Bailey Lewis are Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Foundation Fellows.