Oklahoma Rates 10 in Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Cases

WASHINGTON — When Pam Smith found out her niece had been radio silent for hours, she started to worry. She called family, friends and finally local law enforcement in hopes of hearing good news, or any news at all.

“Before my niece went missing, I knew that the missing and murdered indigenous women epidemic was happening. But I had my head in the sand,” said Pam Smith, whose niece, Aubrey Dameron, has been missing from Oklahoma’s Delaware County since March of 2019.

“When you wake up into this nightmare, you realize how Native Americans are treated differently.”

Smith, her family, indigenous women advocates and search groups from surrounding areas started conducting searches for Dameron, a transgender woman and member of the Cherokee Nation. Local law enforcement did not participate in initial searches as they felt there was no evidence pointing to Dameron being in those areas.

“One of the searches was March 23 and the second was March 30, on one of those we asked if the county could come out with a canine, because we found some red flags,” said Smith. “The county said, why we’re not doing the search, and that was that.”

Capt. Gayle Wells of the Delaware County Sheriff’s Office confirmed her account.

“There was absolutely no evidence of Aubrey being in places they searched. They just picked areas to search, which was fine, I understand their concern,” said Wells explaining the decision to not join the search. “The other side of the coin is we have a very small agency here with very limited personnel.”

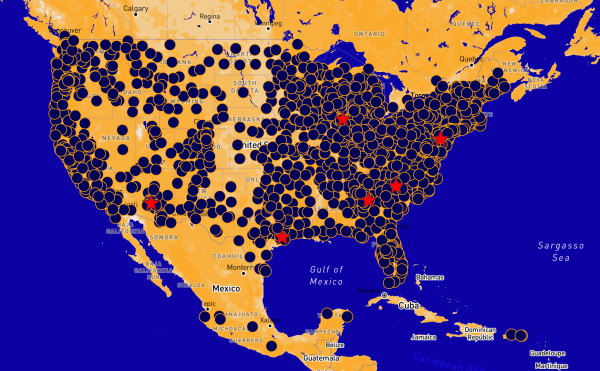

Currently there are 18 missing and murdered indigenous women cases in Oklahoma City and Tulsa: eight murders, six missing women and four of unknown status, according to the Urban Indian Health Institute. Oklahoma has the 10th-highest number of missing and murdered native women in the nation.

The study only reflects cases the Urban Indian Health Institute could find from freedom of information requests, talking to families and willingness of law enforcement to help. Currently, no database exists to collect, track, record or share information on missing or murdered indigenous women cases, which span across tribal, state and federal jurisdictions.

More than four out of five Native Americans, or 83 percent, face some type of violence in their lives, according to the National Institute of Justice, a research arm of the Department of Justice. Fifty-six percent of indigenous women have been sexually assaulted. Of those victims, 97 percent report at least one act of violence committed by a non-Native.

“This is an issue that has been plaguing Native American women for 500 years. And, you know, people need to understand that this is a very deep-seeded issue. It’s not something that just popped up over the last 30 or 40 years or something. It has its tentacles in Native communities and urban areas,” said U.S. Rep. Deb Haaland (D, NM).

The Not Invisible Act of 2019, which passed the U.S. Senate on Wednesday, introduces measures for interagency communication, prevention efforts, specialized law enforcement training and working with tribes to combat the rising numbers.

“The act essentially establishes an advisory committee on violent crime. And the advisory committee would be made up of law enforcement, tribal leaders, federal partners, service providers, survivors or their families or victim advocates,” said Haaland, sponsor of the bill that has moved to the U.S. House.

“They can then make recommendations to the Department of the Interior and the Department of Justice. It also establishes best practices for law enforcement,” she said.

Creating a database for missing and murdered native women is no different than has been done for other areas.

“I just think we’ve created databases in a lot of other areas, I can’t imagine the challenges here are different, maybe a little unique in some ways, but we just have to provide the same level of services to Indian country that we provide in any other part of the country,” said U.S. Rep. Tom Cole (R, Okla.).

“There are a lot of different things that need to be done, but probably the number one thing would be enhancing the authority of tribal law enforcement, and frankly also providing the resources to help increase the professionalism of both those law enforcement units and tribal courts they serve,” said Cole, a co-sponsor of the bill. “It’s going to take a significant investment in the justice part of tribal governance.

“If nobody thinks about these kinds of problems systemically and across the breadth of Indian Country, which is very diverse and difficult to legislate for, you’re going to have these gaps and you’re basing legislation on very incomplete information,” said Cole.

The effort on the federal level comes at the same time Oklahoma legislators are moving to address the missing and murdered issue.

Ida’s Law, named after Cheyenne and Arapaho citizen Ida Beard, who has been missing since 2015, seeks to improve data collection, secure more federal funding to combat crimes against Indigenous women, help families navigate the justice system and create a liaison position for better communication between tribal communities and state and federal agencies.

“We don’t have a lot of good accurate data when it comes to this particular crisis chain. And with bipartisan support in the House, we’ve been able to develop legislation to address that,” said Oklahoma State Rep. Daniel Pae, co-sponsor of the bill which is awaiting approval in the State Senate.

“Ida’s Law would create a liaison position to work with the FBI and federal counterparts when it comes to cases of missing and murdered indigenous people.”

In early November of 2019, the search party for Dameron consisted of volunteers and law enforcement officers, and search dogs got a hit on a plastic tarp. The Sheriff’s office sent the tarp in December to a lab in Cherokee county.

Neither the family or the sheriff’s office has heard back.

“You know, it needs to be out there. People need to know that this is really happening. It’s not just something you’re going to see on TV or read a book. It’s what we’re living,” said Smith.

Gaylord News is a reporting project of the University of Oklahoma Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication.

is a student at the University of Oklahoma Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication and a reporter for Gaylord News.