DACA recipients find community and common ground in advocacy

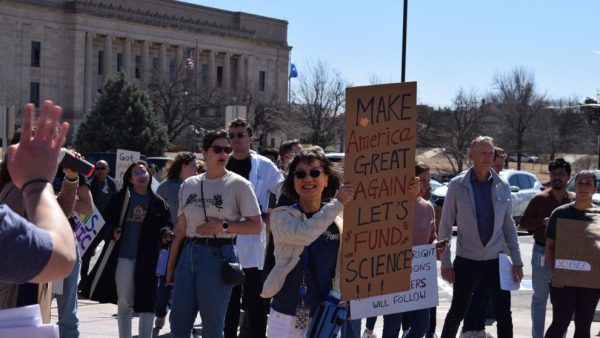

Dozens of individuals hold signs in front of the U.S. Supreme Court on Nov. 12, as a crowd advocates for justices to uphold the Obama-era DACA program. Addison Kliewer/Gaylord News.

Tasneem Al-Michael is the son of parents he admires, the younger of two children, the proud owner of a cat named Moon and the only person in the Al-Michael family who is undocumented.

When he came to Oklahoma City from Bangladesh at 9 months old, his family clutched valuable visas allowing the entire family to reside legally in the U.S. – all except him.

Since he was 14, Al-Michael has been learning how his immigration status makes his circumstances different. Navigating them, he said, can be lonely. He needed answers in 2017, after President Donald Trump began trying to shut the DACA program down, but didn’t know where to look.

“For me, there was only so much my University could do to help me out,” Al-Michael said, referring to the University of Oklahoma. “My parents only knew so much, and, you know, most of my friends, they are documented, so at the time, they just, they didn’t know.”

Finding a community who understood his dilemma was essential, especially with his protections hanging in limbo.

On June 18, the U.S. Supreme Court gave Al-Michael, like thousands of other DACA recipients, a breather by ruling that government explanations for ending their protections were insufficient.

While this decision provided temporary security, it still left many questions for DACA’s future unanswered.

The program was launched in 2012 by President Barack Obama in response to a decade of failed congressional negotiations over the United States’ undocumented youths. Under the order, almost 700,000 recipients, who came to the U.S. as children, are legally able to live in the country for a renewable two-year period.

“DACA opens doors, and it affords us some level of privileges that other folks don’t have,” Al-Michael said, referring to undocumented individuals who do not qualify for the program.

Without it, he wouldn’t be able to work or pay for his college education.

In 2017, President Donald Trump, responding to pressures from nine state attorney generals, decided that Obama had overreached his authority in creating DACA and acted to rescind the program.

Al-Michael remembers that day well.

“I didn’t necessarily know, like, how to cope, or how to understand what to do or how I was going to get help because really, nobody had the answers,” he said.

Then, he was invited to speak at a rally organized by acquaintances at OU in support of DACA. From there, his name was tossed around different advocacy groups, and his network grew exponentially.

When arguments in the lawsuits filed against Trump’s plan to end DACA were heard by the Supreme Court in November, 2019, Al-Michael flew to Washington, D.C., to join DACA recipients rallying outside the courthouse.

Angelica Villalobos was also at that rally.

She came to Oklahoma City from Mexico when she was 11 years old, and like Al-Michael, she has a mixed immigration status family.

For Villalobos, who is an organizer for Dream Action Oklahoma (an Oklahoma-based advocacy group for immigrants), it was important to make the trip to DC so that she could be at the forefront of the DACA case. The Supreme Court’s decision would determine whether or not she faced immediate threat of deportation and separation from her American-born children.

“I have a 19 year-old girl, and we talked about, you know, if we end up in this situation, you might have to be the legal guardian of your siblings,” Villalobos said in November. “Back in 2017, when they terminated the program, she was not even old enough to, but we were already having this conversation.”

Al-Michael’s parents had faced similar fears, inciting them to keep their son’s immigration status from him until he was 14.

“Many families who have gone through that experience just don’t talk about it. You know, this is dangerous, but in most cases they certainly felt like they had no other choice,” said Robert Ruiz, president of Scissortail Community Development Corporation, located in Oklahoma City.

According to a University of Southern California and Center for American Progress study from 2017, more than 8 million U.S. citizens live with at least one undocumented family member. For many of these families, the Supreme Court’s opinion came as a relief.

Al-Michael explained that the Court’s June decision did not end the need for the advocacy work being done on behalf of undocumented immigrants. His community, he explained, is still at the forefront of political importance.

Earlier this month, Trump announced that his immigration plan – set to be announced next month – would address DACA. The plan, which he intends to include in an executive order, will have some protections for recipients and potentially a pathway for citizenship, according to a Telemundo interview.

“From here, it’s also talking about and building the narrative of why DACA recipients, and immigrants are good for everybody,” Al-Michael said. “We don’t necessarily have to prove that to anyone, but like, we’re here and we’re here to stay.”

Al-Michael feels the most unifying experience within his DACA community is the immense pressure to be political.

“It’s not necessarily that our identities are political. It’s just our identities are being made to be political, so we have to be political, no matter what,” he said. “The pressure to be a spokesperson on pretty much all issues regarding immigration and whatnot falls on DACA recipients.”

Gaylord News is a reporting project of the University of Oklahoma Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication.

is a journalism and political science senior at the University of Oklahoma, where she has written for the "Exiled to Indian Country" series and helped cover the U.S. Capital for Gaylord News.