WASHINGTON – For decades, the definition of “waters of the United States” has been a contentious issue, with multiple administrations trying and failing to settle which waters fall under federal jurisdiction.

Last week was no exception.

On August 29, the Biden administration amended its previous 2023 definition of Waters of the United States to conform with a Supreme Court’s June decision and provide additional clarity as to which waters are federally protected.

The revision was the latest in a series of Waters of the United States (WOTUS) policy shifts — a legislative tennis match that has left Oklahoma farmers and developers in limbo.

“This (…) political whiplash of this back and forth of how these terms are being defined really causes a lot of confusion out in the countryside,” Michael Kelsey, executive vice president of the Oklahoma Cattlemen’s Association, said. “Congress really needs to step in.”

‘A political hot potato’

In January, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Department of the Army published a final rule revising the definition of “waters of the United States” pursuant to the Clean Water Act, which was enacted by congress in 1972 “to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters.”

Under the Clean Water Act, the agencies’ regulatory jurisdiction is restricted to navigable waters, or “waters of the United States, including the territorial seas,” according to the act. However, the definition of “waters of the United States” is far from set in stone.

Over the past eight years alone, the regulatory definition of WOTUS has been modified five times — once in 2015, 2019, 2020 and twice in 2023.

“Each president in recent memory has come up with a different rule of approaching (WOTUS) and different definitions and so it makes it very hard to operate,” Rodd Moesel, president of the Oklahoma Farm Bureau, said.

“There’s no stability and no certainty at all.”

In 2015, the Obama administration expanded EPA’s jurisdiction over wetlands by defining WOTUS as any water bodies having a significant nexus — a connection that significantly affects another water body’s chemical, physical or biological integrity — to traditional navigable waters, interstate waters or the territorial seas, according to the rule.

Under this rule, farmers using land near wetlands and streams were restricted from planting certain crops or utilizing certain plowing methods. They also had to obtain EPA permits to use chemical pesticides and fertilizers that could run off into those bodies of water.

Four years later, the Trump administration overhauled the Obama rule, viewing it as a federal overreach that impinged on the rights of landowners, farmers and real estate developers to use their land as they wished.

The 2019 repeal rule kept some federal protections of larger bodies of water, the rivers that drain into them and directly adjacent wetlands, but stripped protections of “ephemeral” streams (streams that run only during or after rainfall) and wetlands not adjacent to or sharing a surface connection with major bodies of water, according to the rule.

In 2020, the Trump administration replaced the 2019 Rule with the Navigable Waters Protection Rule (NWPR), which further refined the definition of WOTUS.

Now, the definition has changed once again under the Biden administration.

“This issue just keeps bouncing around and we never get a solid decision one way or another,” said Clay Pope, an agriculture producer from Loyal, Oklahoma, and former executive director of the Oklahoma Association of Conservation Districts. “It’s become such a political hot potato.”

‘We’re just trying to survive’

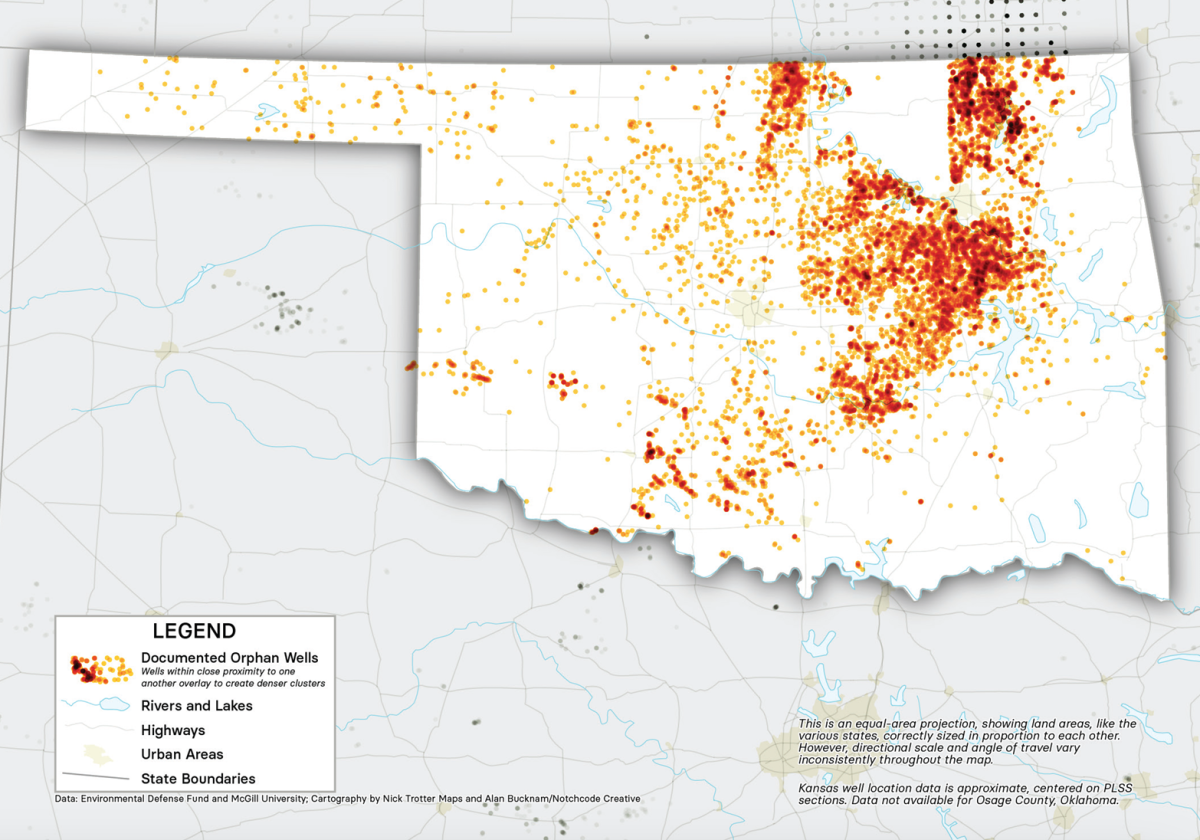

This back and forth with defining the scope of WOTUS under the Clean Water Act has led Oklahoma farmers and industries to constantly question what they are able to do with their own land.

“We’re just trying to survive,” Kelsey said about cattlemen in Oklahoma. “And yet you don’t know for sure what is EPA, how is EPA going to define water to the U.S. today, it may be different than how they defined it yesterday.”

Similarly, with the significant nexus standard, EPA’s jurisdictional power over a piece of land could change overnight. With a spout of heavy rainfall, a field could turn into a wetland that falls under the Clean Water Act’s protection.

“All this uncertainty certainly interferes with people’s decision making and planning and in what to do,” Moesel said. WOTUS is “a source of great irritation to a lot of (Oklahoma Farm Bureau) members because they view it as extreme government overreach, intruding into decisions they would make on their own farm or ranch.”

While many environmentalists push for federal regulation as a necessary measure to protect the country’s water and prevent pollution, Moesel said a one size fits all solution fails to recognize the country’s diverse geography and environmental needs.

“I find lots of problems with these rules when we try to make a rule that applies to the whole nation,” Moesel said. “(Farmers) know their own land best… They understand their land and their climate and are the best managers of their property.”

Jason Vogel, a professor at the University of Oklahoma School of Civil Engineering and Environmental Science and director of the Oklahoma Water Survey, said there are incentive programs in place in Oklahoma that encourage farmers to follow good environmental practices, such as the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program.

The reserve is a voluntary land retirement program that leverages federal and non-federal funds to target specific State, regional, or nationally significant conservation concerns, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Farmers and ranchers who participate in the program are paid an annual rental rate along with other federal and non-federal incentives in exchange for removing environmentally sensitive land from production and establishing permanent resource conserving plant species, according to the Department.

“In Oklahoma, there is a pretty rich history of those types of things working,” Vogel said. “There’s more than one way to help us protect the environment, and Oklahoma has shown that (it) can do that pretty well.”

‘Congress really needs to step in’

The inconsistency of WOTUS was only exemplified by the latest revision in August, which occurred just seven months after the previous ruling.

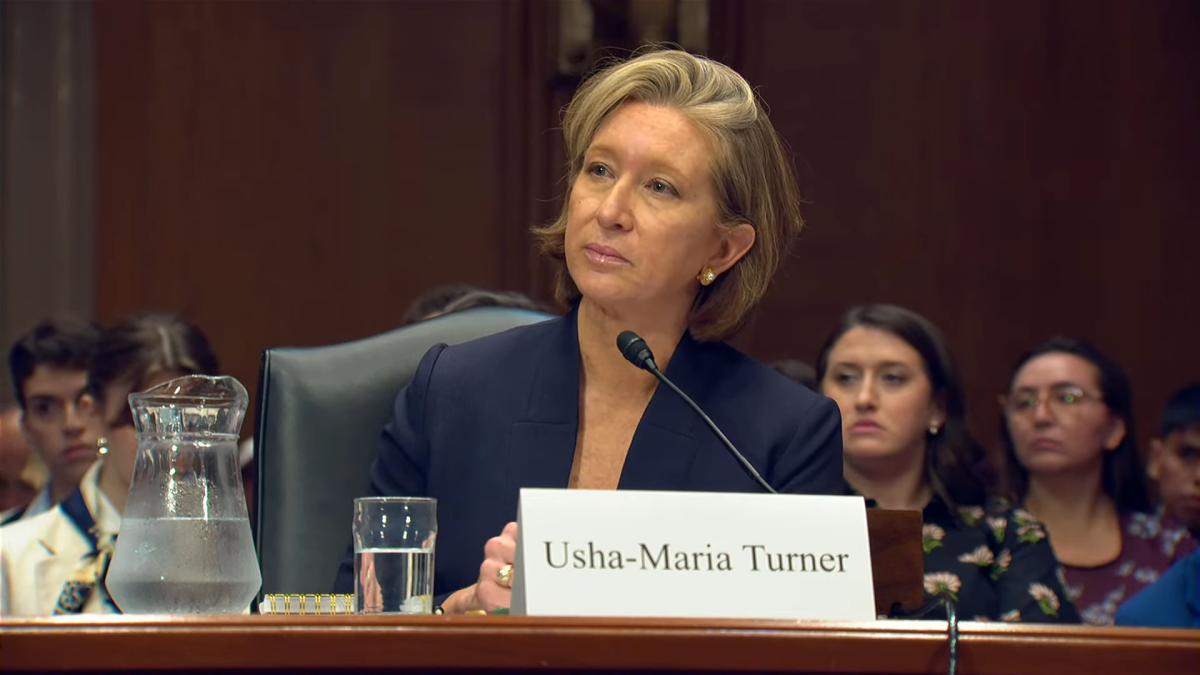

The revision was created to comply with the May Supreme Court decision in favor of Sackett in Sackett v. EPA, a case involving a family trying to build a home on their property near Priest Lake, Idaho, only to be told by the EPA that their property contained wetlands that are federally protected under the significant nexus standard.

Rather than issuing a new rule, the agencies deleted parts of their January rule, including the controversial significant nexus standard, and narrowed the scope of waters subject to federal regulation under the Clean Water Act.

Still, many Oklahomans believe there remains a great deal of uncertainty as to what falls under the category of “waters of the United States” that are federally protected.

“This last issue of the rule, we think, is a very good thing. It’s a positive step forward,” Kelsey said. “We still have a lot of work to do, though.”

Gaylord News is a reporting project of the University of Oklahoma Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication. For more news by Gaylord News go to GaylordNews.net.