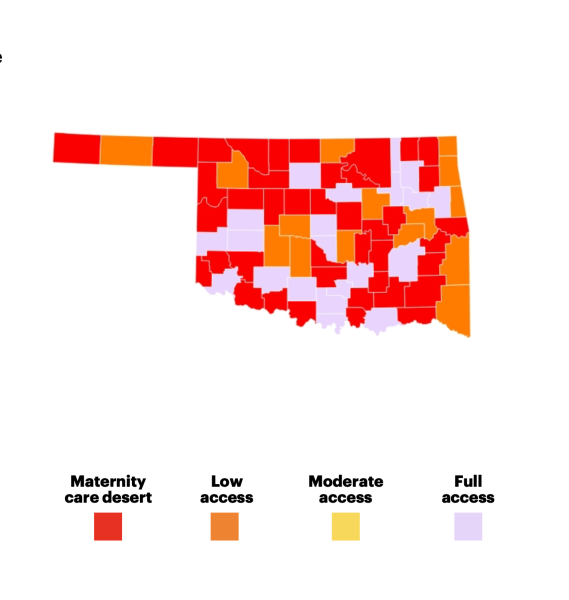

Fifty-one percent of the state of Oklahoma is classified as a maternity care desert, or an area without a single birthing facility or obstetric clinician. This statistic makes Oklahoma’s rate of maternity care deserts the third-highest in the nation, according to a report released in September by the March of Dimes.

Alysia Davis, a March of Dimes national director for collective impact, said what is happening in Oklahoma is similar across the country in that it takes too long for mothers to access care. She said Oklahoma lacks clinicians, and a high rate of people are uninsured, further impacting access.

“There’s also a high rate of families who are living 200% below the federal poverty line, which also impacts the social determinants of health and access to transportation, child care, all of the systems that we know are also just as important to someone’s health and well being as them receiving care,” Davis said.

Only North and South Dakota rank worse than the Sooner State. Even women in Puerto Rico have better access to maternity care than women in Oklahoma, according to the March of Dimes report.

Dr. Kinion Whittington, an obstetrician-gynecologist from Durant who is a member of Oklahoma’s Maternal Health Task Force, said some patients with high-risk pregnancies go out of state to Texas or Arkansas.

Davis said inadequate healthcare during pregnancy can lead to premature babies that need additional care, potentially putting a strain on the family financially and emotionally.

“Looking at how many hospital beds and how many NICUs (neonatal intensive care units) there are in a state; now, will we have NICUs that just don’t have the capacity to see all of the babies coming through?” Davis said.

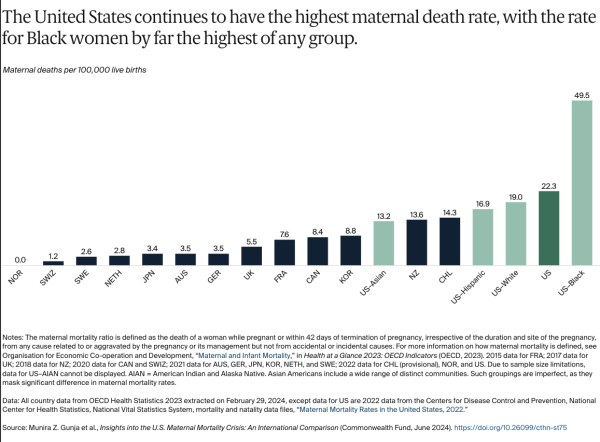

Oklahoma has an infant mortality rate of 6.9 per 1,000 live births, while the nation’s rate is 5.6. Along with the risk of infant mortality, which refers to babies that die before their first birthdays, Oklahoma has a maternal mortality of 29.6 out of 100,000 births compared to 23.2 in the U.S., according to the March of Dimes Oklahoma report card.

The Maternal Mortality Review Committee’s chairman, Chad Smith, said that historically, the causes of maternal mortality in Oklahoma are either potentially preventable, such as managing postpartum hemorrhage or hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, or those that are less so.

“Really, the name of the game as it relates to managing and mitigating risk from those two issues is avoiding what we call denial and delay, so denying that there’s a problem and then a delay in aggressive therapy,” Smith said.

“As you then start to look at access to care and patients having to drive long distances, you can start to see how that kind of can contribute to some of the challenges we deal with in the state of Oklahoma around maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity (health conditions during pregnancy or postpartum that affect the mother),” he said.

Whittington said the small town of Idabel in far southeast Oklahoma no longer has maternity services, requiring people to drive 60 miles or more to see an OB-GYN .

“What happens is, as the physician population contracts, and the numbers of deliveries contract at a facility, they get to a point where they really can’t keep staff trained and do a very good job, and it just kind of dries up,” Whittingon said.

Since Idabel stopped offering maternity care, Whittington has seen an influx of patients not only needing OB care but gynecological care in general. He said the patients have to drive 40 or 50 miles to his clinic in Hugo, with the nearest labor and delivery hospital another 50 miles from Hugo.

“I saw essentially a terminal cervical cancer this week just because she did not have access to care like most people do that live in urban areas,” Whittington said.

Whittington said Oklahoma Health Care Authority is doing well mitigating the issue through holding the medical care organizations accountable and having the best interest of the Oklahoma citizens that are on SoonerCare or Medicaid. But he has seen a 30% decrease in revenue from his patients on public assistance, and he is not alone.

“I know a practice just laid off some mid-levels (a provider with less training than a physician but more than a nurse) because they, frankly, just can’t pay them, and these are practices that serve underserved populations, so that’s the areas that we really need to focus on,” Whittington said.

He said he has recently talked to physicians who are at the point of stopping practice and moving or limiting their services because of non-payment or slow payment.

When it comes to medical students eventually practicing in rural areas, Whittington said someone from a rural area has a higher chance of moving back to a rural area. The OB-GYN said the state and nation will have to look at getting trained nurse midwives to rural communities with a team approach.

Davis said the March of Dimes has considered factors impacting health and well-being besides medical providers; for the nation to see change, interventions should be implemented like telehealth, changing insurance payment models and policy.

Last April, Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt approved Senate Bill 1739, which eliminates the licenses for birthing centers and modifies the insurance criteria for postpartum care. Less than a month later, the governor approved House Bill 2152, reducing the Maternal Mortality Review Committiee’s membership, requiring reasonable effort to report maternal deaths within 72 hours, investigating these deaths and reporting the conclusions to the MMRC.

“I truly believe that if we’re working on both of those together at the same time, we’ll really see a domino effect because while we’re changing policies, we’re changing practices,” Davis said. “Then we are now creating communities where moms and babies not only have access to what they need, but it’s their right.”

Gaylord News is a reporting project of the University of Oklahoma Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication. For more stories by Gaylord News go to GaylordNews.net.