MINNEAPOLIS, Minnesota ー Anthony Brutus Cassius, or A.B. Cassius for short, is known as a civil rights leader whose contributions to the Black community in south Minneapolis is still revered a hundred years later. But his origin story, tied to the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, is part of his story that is less known and cloaked in some mystery.

The biggest mystery of the Cassius story is when he left Oklahoma and how tied his story is to the history of the Greenwood District, a largely Black community that was destroyed during a bloody and fiery three days in 1921.

According to historical entries from the U.S. Census Bureau, Cassius was born on June 29, 1907 in Guthrie, Oklahoma, about an hour and a half away from Tulsa. His parents, Samuel Robert and Selina Cassius, were both former slaves, from Virginia and Texas respectively. Samuel Cassius, himself, was an author, farmer, Church of Christ minister, and politician. A.B. Cassius was one of at least 12 children, but it is believed the number could be as high as 23 children.

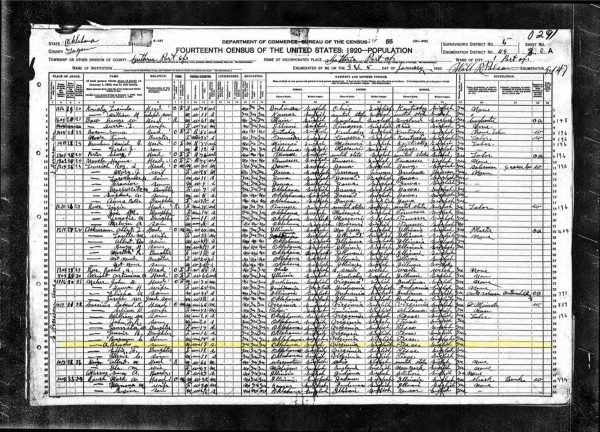

The 1920 census shows Cassius, seven of his siblings and his parents living in Guthrie. After 1920, Oklahoma became plagued with racial violence more than ever before, and the Cassius family seemingly all dispersed, with only a couple of Cassius’ siblings being found in any government documents in Oklahoma afterward.

Black families scattering north after the massacre was a common reality, according to Victor Luckerson, author of the book Built from the Fire that chronicles Greenwood District’s history from before Oklahoma statehood.

“[Families] likely followed the main routes of the train tracks, since that dictated a lot about how people moved around the country back then,” said Lukerson, “So cities like St. Louis and Chicago probably took on a lot of refugees.”

Cassius and his brother, though, were headed to a different place.

Samuel Cassius put A.B. and his younger brother Benjamin, on a train headed north sometime in the early 1920s. Their first stop was in Omaha, Nebraska.

“We walked around the city of Omaha all afternoon and we didn’t like it,” said Cassius in his 1981 oral history interview conducted for Twentieth Century Radicalism in Minnesota. “We had about seven dollars between us and we decided to come to the Twin Cities.”

Cassius landed in Minneapolis at the age of thirteen. His early life consisted of going to school and sleeping on a mattress in the basement of the hotel where he worked. By the time he graduated from high school, he was at the top of his class and a star football player. He should have been headed to college.

“But the chance of a Black man getting a scholarship to a college was nil,” said Cassius in the 1981 interview.

Following in his father’s footsteps, Cassius started school to become a minister, but after a year he decided to leave. Married with two children, Cassius ended up working multiple jobs in clubs and cafes as a waiter. After finding out his white counterparts earned $75 a month, versus his $17, he decided to form a labor union.

“This can’t be right,” said Cassius. “We working here ‘cause our faces are black for seventeen dollars a month. So I attempted to organize.”

Eventually, the union won $500 worth of backwages for some members. He continued to be active in the labor movement throughout his life.

In 1937, Cassius bought a building on 38th Street and 4th Avenue South and named it Dreamland Café. The name Dreamland represented exactly what this place meant for the Black community in Minneapolis. It was a place where people ate, drank beer, relaxed and felt safe. A social dreamland where their future had every possibility.

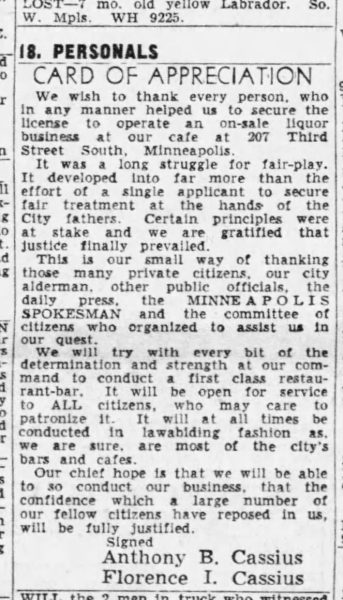

In the late 1940s, Cassius decided he wanted to own a different business. But he needed something no other person of color had obtained in the Twin Cities – a liquor license.

When he first applied for the license, Cassius was told that Black people could only operate barbecues, shoeshine parlors, and barbershops. Blacks needed to prove they were not going to use their business for “immoral purposes.” The FBI questioned whether Cassius was a communist and claimed he had been to Russia even though he had never been outside of the United States.

After a two-year battle, Cassius became the first Black man with a liquor license. He then walked into Midland bank, liquor license in hand, and was approved for a $10,000 loan. The Cassius Bar became a reality.

Owning these businesses and working to improve civil rights led to Cassius being known as “The Godfather of Dreamland” and “The Godfather of Black Space in Minneapolis.” On June 20, 1980, Cassius closed his bar for good, after multiple relocations throughout the southside of Minneapolis.

Cassius left behind a legacy of Black economic success after his death on August 1, 1983, something that he saw destroyed near his home when he was young during the Tulsa Race Massacre.

Cassius still inspires people in Minneapolis. A ten-million dollar development titled “Dreamland on 38th” is in the early stages. The joint venture, by the Cultural Wellness Center and entrepreneur Dr. Freeman Waynewood, has the potential to see a new cultural district in Minneapolis for African-Americans.

Over a hundred years after the Tulsa Race Massacre, Cassius’s commitment to building a strong Black community on the south side of Minneapolis continues on into the 21st Century.

Return to the Voices of Resilience homepage.