MINNEAPOLIS, Minnesota ー The term “dreamland” evokes visions of hope, aspiration, and a safe haven where dreams can be realized. For many Black communities, particularly during the early- to mid-20th century, “dreamland” symbolized a space of cultural, social, and economic sanctuary in a time of segregation and racial hostility.

In prominent Black cities, such as Tulsa, Oklahoma; Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Chicago, Illinois, prominent Black-owned institutions held the name of Dreamland during the early 1900s. These establishments not only provided entertainment and social spaces but also played crucial roles in fostering Black community resilience.

Here are examples of Black-owned ‘Dreamland’ businesses and the history surrounding them.

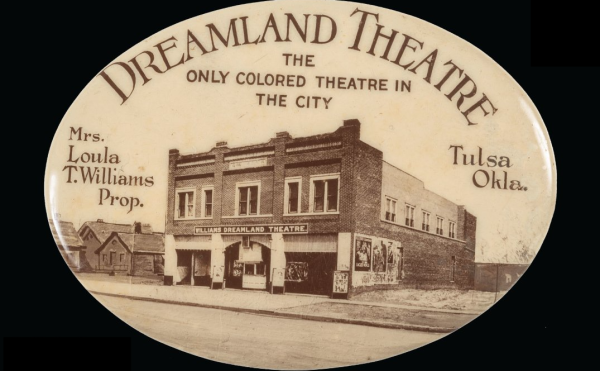

Dreamland Theatre

Opened on August 30, 1914, in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, the Dreamland Theatre was more than just a theater for many residents of Tulsa. It was a cultural hub. Owned and operated by Loula Williams, the theater offered a space where Black residents would enjoy live music, silent films and other forms of entertainment in their segregated society. With a seating capacity of 750 and central cooling – a rarity in the day – the theater was a significant cultural establishment in the heart of “Black Wall Street.”

Tragically, the Dreamland Theatre was in the center of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, a devastating, racially charged mass killing that saw 35 city blocks of Greenwood burned to the ground, including the theater.

During the days-long chaos, the Dreamland Theatre served as a gathering point for community members seeking to organize and protect their neighborhood, and also served as a makeshift shelter. Despite what happened in 1921, the theater was later rebuilt as the New Dreamland Theatre, continuing to operate into the 1950s and sustaining its legacy within Black culture in Tulsa.

Williams’ dream of a movie theater franchise in Oklahoma was crushed, though, from the massacre.

Once a strong and vibrant business owner, Williams’ health and finances suffered deeply from the massacre. She died in 1927.

Dreamland Café in Minneapolis

The Dreamland Café in Minneapolis, established by Anthony B. Cassius in 1937, was one of the first social spaces for Black Americans. Although the cafe attracted headliners like Nat King Cole, it was also a necessary community center. The establishment provided a rare environment where Black Minneapolis residents could gather, socialize and connect within a segregated society. The Dreamland Café served for years as a place where people could go, relax and dream of the life they could one day lead, when not limited by the color of their skin.

Cassius would go on to open other cafes and bars throughout his life, becoming the first Black man to obtain a liquor license in Minneapolis. All of his businesses would serve as a gathering place for Black people in Minneapolis. After years of work committed to entrepreneurship and civil rights, Cassius died in 1983 and left behind a legacy of inspiration for Black entrepreneurs.

Dreamland Café in Chicago

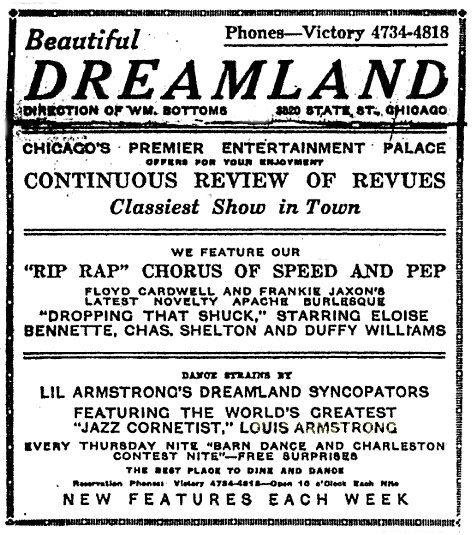

The Dreamland Café in Chicago’s Bronzeville opened on October 7, 1914. Three years late, Bill Bottoms took over management. The venue became a premier site for jazz on the South Side hosting legendary musicians such as Louis Armstrong, Joe “King” Oliver and Sidney Bechet. Not only was the Dreamland Café integral to the development of early 20th-century jazz, it was a cultural institution that provided a platform for Black artists and a safe social space for the Black community in Chicago.

Chicago Defender ad promoting Louis Armstrong at the Dreamland Café in November 1925.

According to a Indiana Jones wiki fan page, the Dreamland Café in Chicago is a mention in Indiana Jones and the Genesis Deluge, the fourth book in an Indiana Jones book series.

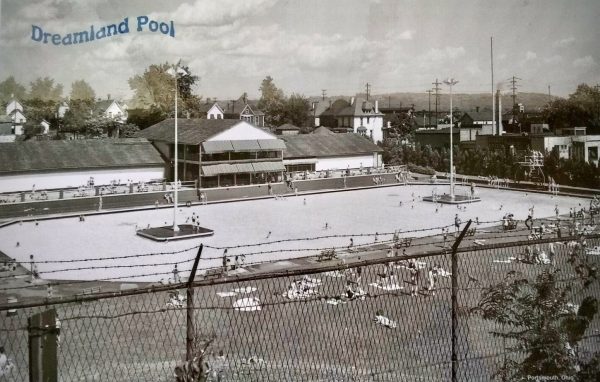

Dreamland Pool

The Dreamland Pool in Portsmouth, Ohio, also holds a significant place in the history of Black resilience and the fight for civil rights. By the summer of 1964, the Dreamland Pool was a private club called the Terrace Club. Being in the middle of the civil rights movement, the pool was still segregated.The local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), led by Charles Stanley Smith, Jr., orchestrated a “wade-in” on July 17, 1964, to challenge this segregation. The peaceful protest saw Black demonstrators entering the pool, only to be arrested and taken into custody.

This direct action was a turning point in the city’s history. Despite legal threats and the complexities of local and federal laws, the protest led to the eventual integration of the pool by the following summer. Renamed to Dreamland, the pool became a symbol of the end of segregation. The Dreamland Pool thrived into the late 1960s and early 1970s, before eventually closing in 1993.

Dreamland on 38th

Today, the legacy of these historic Dreamlands is being revitalized in Minneapolis through a new project: Dreamland on 38th. Inspired by the original Dreamland Café owned by Anthony B. Cassius, the development aims to create a cultural and economic anchor within the 38th Street Cultural Corridor. Dreamland on 38th will offer flexible workspaces for Black entrepreneurs, particularly those focused on the intersection of food and heritage. This project hopes to honor the legacy of A.B. Cassius by fostering social entrepreneurship and community building, much like the original Dreamland Café.

From the Loula Williams’ Dreamland Theatre in Tulsa, which stood resilient in the face of destruction, to the Dreamland Café in Minneapolis, which provided sanctuary and joy, to the significance of the Dreamland Pool in the civil rights movement, the title Dreamland reaffirms the importance of such spaces in nurturing the dreams and potential of the Black community. The word “dreamland” thus remains a powerful emblem of hope, resilience, and the enduring quest for a better future.

Return to the Voices of Resilience homepage.