Oklahoma’s largest museum of natural history is also one of the largest holders of the remains of Native American and funerary objects in the country.

Now, 25 years after passage of law requiring remains be returned to families, the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History on the University of Oklahoma campus is hiring a coordinator to oversee repatriation efforts of Native American remains it holds under the Native Graves and Repatriation Act.

The museum’s holdings represent the 18th largest collection of unrepatriated remains in the nation with over 3,800 Native American remains and more than 115,500 associated funerary objects, according to ProPublica.

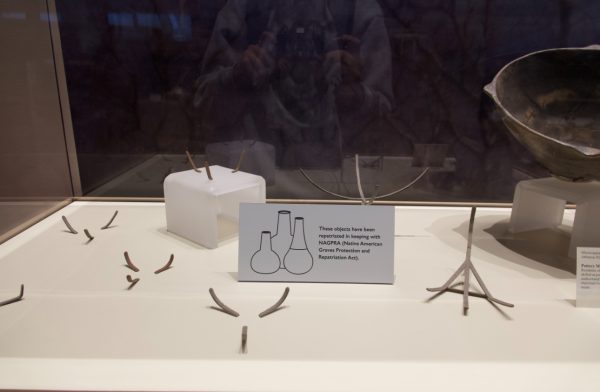

Since 1990, there have been federal protections in place for Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects and objects of cultural patrimony. By enacting the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, Congress recognized that human remains of any ancestry “must at all times be treated with dignity and respect.”

Visitors to the Sam Noble museum will find only a fraction of its Native American collection in the McCasland Foundation Hall of the People of Oklahoma, according to according to Marc Levine, associate curator of Archaeology at Sam Noble and associate professor in the OU Department of Anthropology, who said the exhibit was built with support from the tribes.

“The idea of an antagonist or competitive relationship between the museum and the tribes does not exist,” Levine said, “It is more so collaborative.”

Since the inception of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, the museum has repatriated artifacts to Caddo Nation, Osage Nation, Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, Chickasaw Nation, Choctaw Nation, Muscogee (Creek) Nation and continues to work closely with the state’s tribes.

Between 2011 and 2024, the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma conducted four repatriations from the museum. These included more than two dozen ancestors and more than 200 associated funerary objects.

“The Sam Noble staff have been great to work with, always willing to answer questions promptly and efficiently. They’ve been very respectful and professional when ancestors are physically returned to Choctaw Nation, and that is very much appreciated,” said Ian Thompson, Tribal Historic Preservation Officer at Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.

While the museum works to take inventory and repatriate the cultural items and ancestors in its collection dates back several decades, the museum’s staff began to emphasize the importance of NAGPRA compliance in the mid-2010’s.

“Those efforts, which included building important relationships with National Park Service staff, applying for NAGPRA-compliance grants, requesting expert consultants, and raising NAGPRA awareness on campus, laid the foundation for the University’s maturing NAGPRA compliance program,” said Tana Fitzpatrick, OU’s associate vice president for tribal relations.

While the museum works to take inventory, consult, complete inventory and repatriate the cultural items and ancestors in its collection dates back several decades, the museum’s staff began to emphasize the importance of the Repatriation act’s compliance, both in letter and in spirit, in the mid-2010’s.

“NAGPRA compliance and respecting tribal relationships is a priority for the University,” she added.

Stowed away and hidden from the public, the fifth floor of Sam Noble carries the dimly lit shelves that hold all the related artifacts and remains accumulated over years of research. Some items sit neatly preserved, awaiting study or display, while others remain miscategorized, collecting dust in archival boxes. In these silent corridors, history lingers.

The inventory in these archival collections can sometimes still be found in its original brown paper sack, dating all the way back to the 1930s. This is a testament to Works Progress Administration America, where some of the public works efforts completed during this time included mitigating archaeology, excavating burials and granting museum possession of these goods but not for the purpose of exhibition.

Just like any attitude or policy is subject to change, Levine opens up the question, “Is the consent that was (provided) in the ’90s for perpetuity? Is it forever, or is it something that needs to be updated?” Currently, he ensures there is regular contact with tribal representatives and an open line of contact.

The museum has the largest archaeological collection in the state of Oklahoma that includes millions of artifacts and is actively engaged in repatriation work.

“In 2024 alone, we prepared a total of 751 sets of ancestral remains and 1,588 funerary objects for repatriation. By this measure, we are probably among the most active NAGPRA programs in the country,” Levine said. “There is still a great deal of work to do, but we are on the right track,” he added.

In 2023, the OU Provost appointed an independent NAGPRA Oversight Committee, representing scholars in the fields of anthropology, archaeology, art history and Indigenous law, to provide advice and recommendations to the University, including the museum, on Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act related matters. This decision was made in conjunction with a $16,765 grant in American Rescue Plan Act funds to support repatriation work at the museum.

“Currently, the Oversight Committee is: 1) developing a central NAGPRA communication line, 2) instituting a survey to inventory the University’s collections, and 3) dedicating hours of study to ensure it can serve as a resource to the University in implementing the new NAGPRA regulations, among other priorities,” said Fitzpatrick.

“The museum’s standard of care for ancestral remains and establishing tribal relationships has been, and continues to be, a matter of priority,” she added.

Because OU has historically made necessary efforts to comply with NAGPRA, the slight reorganization of this program will not look much different from the outside- it is a constant and ongoing process. With a delegated coordinator, the project and management administration will be expedited and given necessary attention.

“When family members laid their loved ones to rest, they intended for them to stay at rest forever, not get dug up and accessioned into a collection,” said Thompson.

Kylie Caldwell is a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.

Gaylord News is a reporting project of the Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication. For more stories by Gaylord News go to GaylordNews.net.

To learn more about the First Oklahomans, read Exiled, an OU Project.

To learn more about the Volunteer Office at Sam Noble, click here