WASHINGTON – When Maryam Atayee fled Afghanistan, she left behind her job as a teacher and midwife, her home in Kabul, and the life her family had built.

Atayee arrived in the United States in late August 2021, only a few days before the U.S. completed its chaotic withdrawal from Kabul, first landing in El Paso, Texas. Eight months pregnant and accompanied by her two young children and husband, she spent the next two months living in the Fort Bliss Afghan refugee camp, ‘Doña Ana Village’.

Once her baby was born, the government moved her and her family to Oklahoma. Starting over in the Sooner state was not easy. Atayee spoke limited English, didn’t have a car, and had no idea how to manage appointments, grocery stores, or job applications. With no way to navigate daily life, she relied on Oklahoma churches, local organizations, and federal programs to get by.

“We had nothing with us, no money and no clothes, and nothing to figure out everything,” Atayee said. “We are really happy that we had food stamps to figure out our food and Medicaid for our doctor appointments. Without that, it would have been really hard.”

Federal aid helped Atayee build a life in the United States. Now, the very programs that helped her family find stability are under threat.

Among those proffers was a pledge by Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, who said the state would accept 1,800 Afghan refugees

Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond in June called for the removal of Afghan refugees from the state. Drummond expressed concern about the cost of Afghan refugee resettlement in Oklahoma and questioned whether all of “Sttit’s refugees” admitted through emergency parole were properly vetted.

Last month, President Donald Trump signed his “One Big Beautiful Bill” into law, codifying sweeping domestic policy changes. Among them are restrictions to Medicaid, SNAP and tax credits that help low-income individuals buy private health insurance, from which refugees and other immigrants with legal status are excluded.

Proponents of the changes argue that current refugee policy doesn’t align with national priorities and that vetting procedures are insufficient. The eligibility changes for immigrants are expected to save the government roughly $13 billion over the next decade.

However, refugee service providers in Oklahoma say that many of their beneficiaries rely on these federal programs for support as they transition into American society. Without this aid, they fear refugees will face greater food insecurity, delays in accessing healthcare and increased difficulty enrolling in schools or navigating complex systems.

“It’s inhumane, truly, to welcome people to our country and say, ‘Hey, you’ve just survived war. Welcome to our country. We provide nothing for you to have safety, to have health, or to have your basic needs met,’” said Molly Bryant, senior director of immigrant and refugee services at YWCA Tulsa.

Bryant says many refugees arrive with untreated health issues due to displacement or persecution.

“If you don’t have insurance, you’re going to let these things go until they’re

emergencies,” Bryant said. “It’s an inhumane thing, but it’s also economically a very, very poor choice.”

When one of Atayee’s sons developed a medical emergency, she says the hospital bill came out to more than $30,000, an amount she could never have handled alone. Support from friends, local organizations, and Medicaid helped carry the burden.

Despite funding cuts, local organizations continue to fill in the gaps. These refugee service providers help with everything from housing and healthcare to employment and language training.

Julie Davis, CEO at YWCA Tulsa, said she finds it troubling that policymakers are targeting refugees in particular.

“You know, these are people who are vetted, who come here legally, and who, once they’re here and are paying taxes, become Americans,” Davis said. “They begin their path, and they have status.”

In Afghanistan, the Taliban’s return to power forced many, including mothers like Atayee, to flee. Her experience reflects the story of many refugees, who are often forced to leave their home countries due to persecution based on religion, ethnicity, or political beliefs.

Typically, refugees seek safety by fleeing across an international border, where the UN may register and refer them for resettlement based on factors such as vulnerability, family ties, and host country capacity. In Afghanistan, however, it was a chaotic airlift out of Kabul orchestrated by the International coalition against the Taliban and al-Qaeda that included the U.S., U.K., Canada, Australia, Germany and France among others.

“People often assume that refugees have this pretty simple pathway to the U.S., which is not true,” Bryant said. “Even if you’re selected to come to the U.S., you have to take out a loan through the International Office of Migration. You have to take out a loan for your plane tickets.”

Once in the U.S., a resettlement agency helps refugees find housing and begin the adjustment process.

For Atayee, that meant navigating a new language and health system while trying to keep her children safe and cared for. Support from people like Kelly Osborne, executive minister of the Springs Church of Christ in Edmond, helped fill in the gaps, providing a place for her and other refugees to learn English and even pitching in to cover dental care bills.

“We just try to be in their corner,” Osborne said. “We have people to practice with them, and then we have tea together, so it’s just a common place for them to come and connect.”

The rollout of benefit restrictions varies: Medicaid eligibility ends on October 1, 2026, and healthcare marketplace tax credit exclusions take effect January 1, 2027. SNAP restrictions could take effect sooner, possibly as early as a refugee’s next recertification, according to Global Refuge, a national nonprofit that supports refugee resettlement and tracks policy changes.

After one year in the U.S., refugees can apply for a green card. Once approved, a process that can take months or even years, SNAP and Medicaid eligibility can be approved. While the U.S. offers a refugee medical assistance program, it lasts only four months, leaving a gap in coverage.

“There’s so much happening, like right now today, that is impacting [refugees] that we just have not had time to develop the right amount of strategy for what this means,” said Kim Bandy, CEO of The Spero Project, an OKC nonprofit that provides services to refugees while connecting them with neighbors.

Currently, those explicitly listed as eligible for these federal programs under the “One Big Beautiful Bill” include Lawful Permanent Residents (green card holders), Cuban and Haitian entrants, and individuals from the Compacts of Free Association.

Refugees, parolees, asylees, and immigrants with Temporary Protected Status are excluded.

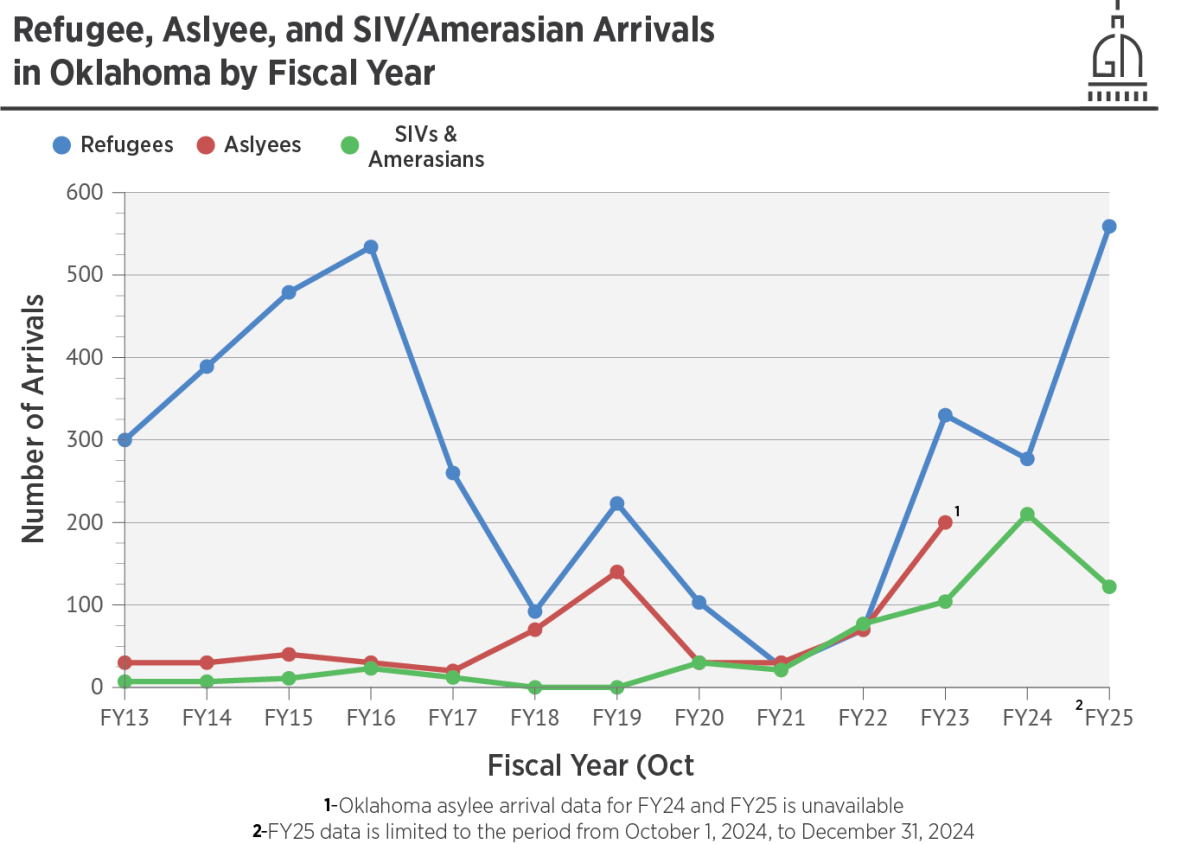

Since October 1, 2012, Oklahoma has received nearly 3,641 refugees and 690 asylees, according to data from the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau for Population, Refugees, and Migration. Many eventually obtain green cards and become citizens.

Additionally, around 624 Special Immigrant Visa holders, primarily Afghans and Iraqis who aided U.S. forces, and Amerasians have been resettled in the state. It remains unclear whether SIV holders will lose coverage, though they are generally treated as green card holders in social programs.

Davis said the Office of Refugee Resettlement and its Oklahoma partners are still finalizing how the rules will be implemented and who will be affected. Detailed procedures are expected closer to the rollout dates.

These changes are just the latest blow to Oklahoma’s refugee system, which has already faced months of disruptions. They come amid a broader rollback of protections, including a pause on resettlement, suspended contracts, funding cuts, and growing threats to the legal status of many immigrants.

“There’s been so much dismantling of the refugee program,” Bandy said. “And there’s been so much challenge with current levels of funding that our reaction right now is fear for our neighbors, and really sadness for our neighbors.”

Bandy says the Spero Project and other providers are developing strategies but will likely need philanthropic support and national coordination to continue.

“We’re looking at what a coalition may look like, nationally and locally, to respond in a way that meets the basic needs of humans that live here,” Bandy said.

Atayee is still waiting for her green card and for her youngest child to start school before she finds permanent work. Until then, she continues to balance caring for her family with the uncertainty of what’s ahead.

As the state determines who will be affected, Atayee and her supporters hope for exemptions or changes that could soften the impact. If not, the help of support groups and friends, such as Kelly Osborne, will become even more essential.

“When I need something and when I’m asking her, she’s helping me,” Atayee said. “I appreciate that. She’s part of my family and she’s in my corner.”

Gaylord News is a reporting project of the University of Oklahoma Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Comunication. For more stories by Gaylord News go to GaylordNews.net.