Residents of Oklahoma City know to get the best pho or exotic fish in town: head to 23rd and Classen. The area is known as the Asian District, but few know the story of how the moniker became official. The family owners of Super Cao Nguyen, the largest international market in the city, dreamed up the idea while oldest son Ba Luong was attending Baylor University in Waco, TX. Luong would travel home on the weekends to help his parents in meetings with city officials. After much persistence, the signage went up in 2004. The Asian District has remained an integral part of Oklahoma City’s cultural diversity.

With this rich cultural region come many stories of hardships and families fleeing persecution in the pursuit of a better life, even the American dream. For Ba’s parents, Tri and Kim, recounting their days as Vietnamese refugees is too painful.

“My parents actually don’t talk about it a whole lot,” Ba Luong said.

Out of the family’s three boys, Ba was the only one born in Vietnam. He was just one-year-old when he and his parents left their home in 1978.

“My parents fled Vietnam as refugees. They decided that they couldn’t live in Vietnam anymore because of the regime there,” he explained, “they had gotten on a fishing boat, got lost along the way and they ended up fortunately in Malaysia.”

The journey to Malaysia was not easy, especially with a baby in tow. When Tri and Kim spotted a big tanker, the ship captain told them he could not accept them.

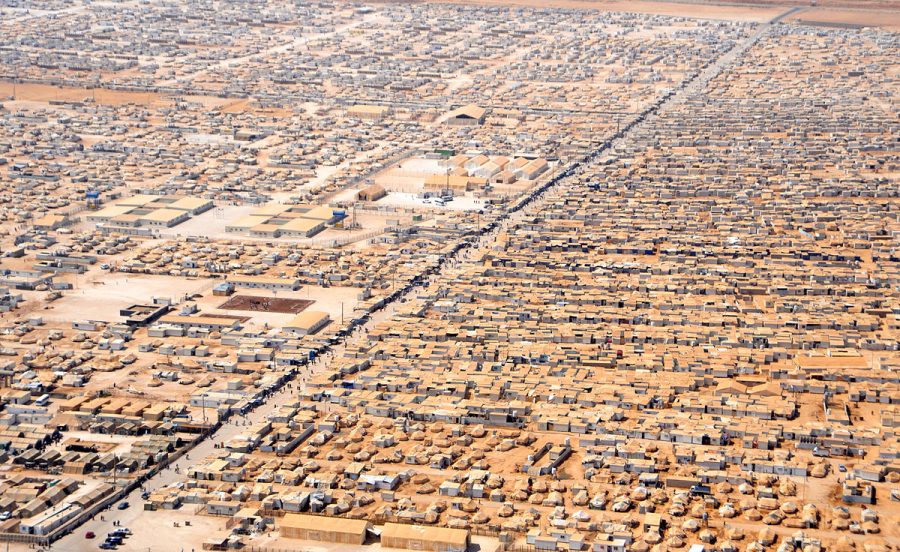

“He told them basically, ‘if you want to become refugees what you need to do is, early in the morning, sink your boat.’ So they sank their boat and he said ‘swim for it’ so they swam towards Malaysia, and they ended up in a refugee camp,” Ba said.

Ba could not relate the specifics of what it was like swimming for their lives with a one-year-old. He says it is a conversation he and his mother have never had.

The Luong family of three remained in the refugee camp only for a couple of months, as many countries were taking on refugees at the time, “Unlike the current political climate,” Ba said.

It was common at the time for churches to sponsor refugees seeking safety in the states. “We were fortunate enough to be sponsored by a Baptist Church,” he explained, “They bought us plane tickets, we flew to the U.S. and landed in Washington, DC July 4, 1978 if you can believe that.”

The Luong family’s start in America was modest at best. The church that sponsored them set up Tri with a small apartment and a job as a dishwasher.

Much like the original refugees that came to the states in 1776, the Luongs ventured further west. To reconnect with friends from Vietnam, the family moved to Fort Smith, Arkansas.

“Go west, young man,” Luong remarked on the similarities between the Pilgrims’ pursuit of religious freedom and his own family’s journey for a safe haven.

His parents found work again as dishwashers, but quickly went on to pursue bigger aspirations.“They longed for some of the foods that they had in Vietnam, so they decided they wanted to open up a little convenience store and service the community there,” he said.

Tri and Kim saved up all of the money they had and purchased a small shop. In order to get the ingredients necessary for authentic Vietnamese food, the Luong family would travel from Fort Smith to a store called Cao Nguyen in Oklahoma City. The food market was only a couple 1,000 square feet at the time.

After a few months of commuting, Cao Nguyen went up for sale. The Luong family again gathered all of their resources to purchase the exotic food store in Oklahoma City. Large expansions were made, the ‘Super’ was added and now the family proudly owns the largest international market in the city.

Super Cao Nguyen attracts many loyal customers from all backgrounds. One man identified as ‘Cowboy Dan’ has been shopping at the supermarket for over 14 years. “There are very nice people and have very good Vietnamese food,” Cowboy Dan said. “They have all the foods here that he likes for me to cook,” his wife Hue said.

Another way the Luong’s give back to the community is by hiring refugees like themselves and giving them the same opportunity they received when arriving in the states. A Burmese refugee, Joseph Thamg, was hired as a cashier at the store soon after arriving in the U.S. “This is my first job and I have really enjoyed working here,” Thamg said.

The legacy the Luong family has left in Oklahoma City is not just one of capturing the American dream, but treading the path for others to do the same.

“If you drive up and down Classen Boulevard and you see the Asian District signs, you see all the development around there, that’s the biggest part,” Ba explained, “I’ve always believed in leaving the world a better place than when you found it. So hopefully we’ve made positive contributions to this city and we’ve spurred additional growth.”

In a time where the world is seeing the biggest refugee crisis in history, stories from the past like the Luong family’s can easily hide in plain sight. “A lot of the refugees still don’t want to talk about the past, they want to focus on the future,” Ba said.

Based on the success of Super Cao Nguyen and its impact on the community, that future is bright.

“Every community, every immigrant and refugee group, has fled to America and they have contributed something to the fabric of this country. So I think before we start making judgments about whether it’s right or wrong – in the current political climate – we need to take a step back and look at the contributions each group has made to this country,” he said.

In a country born out of the need for refuge, all that is needed is one opportunity. The Luong family got that opportunity in 1978, which turned into more opportunities for so many Oklahomans. This family’s story is not political or religious, but inherently human.

“I think the driving force of every human being whether it’s a refugee or a citizen or an immigrant, is that they want to do better, not only for themselves but for their family. They’re working basically for their family, for their future,” he said.