Coronavirus stigma affects pandemic response

A model of the novel coronavirus. Stigma associated with COVID-19 infection has affected how people manage their health and communicate with others. (Gaylord News)

When University of Oklahoma student Leslie Miller’s niece realized in the spring she probably had COVID-19, before it was clear how widespread the pandemic would be, she tried not to talk about it.

Even though there were still many unknowns about the disease, including how it spread, her niece did not want to be stereotyped as someone who parties or acts irresponsibly, said Miller, who is working toward a Ph.D in sociology.

“It’s just the unknown, the fear of the unknown, I think it comes down to,” said Miller, who said this is also seen in diseases such as lung cancer, so that people end up being blamed for being sick.

“Some people get lung cancer and they’ve never smoked, so it’s not their fault,” Miller said.

Now, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues into a ninth month, a perceived “social stigma” is becoming increasingly prevalent. COVID-19 is caused by a member of the coronavirus family that’s a close cousin to the SARS and MERS viruses that have caused outbreaks in the past.

According to the World Health Organization, the outbreak “has provoked social stigma and discriminatory behaviors against people of certain ethnic backgrounds as well as anyone perceived to have been in contact with the virus.”

That’s due in part by the many unknowns about the virus, according to the WHO, and the virus is affecting some communities more than others.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that people in racial and ethnic minority groups can have an increased risk of getting sick and dying from the virus due to “longstanding systemic health and social inequities.”

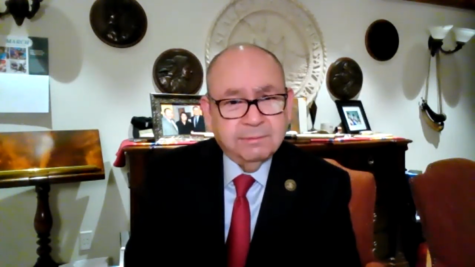

Because of this increased risk, many people associate their own prejudices with the coronavirus, said Michael Givel, an OU professor who researches public policy theory.

“So, unfortunately, not only is the coronavirus a very serious and ugly thing, but then people top it off with their prejudices and discrimination,” Givel said.

Another reason for the stigma is a lack of understanding of the disease, said Miller, who is studying the sociology of medicine and healthcare. But contributing to the stigma may be the current political climate.

Language can have a big impact on fueling stigma, according to WHO. Names such as “Wuhan Virus” or “Chinese Virus” can perpetuate stereotypes and cause ethnic groups identified by the CDC as Asian Americans or Pacific Islanders, among others, to experience stigma. This can “drive people away from getting screened, tested and quarantined,” the WHO says.

Political polarization about mask-wearing can contribute to discrimination, Miller said.

“(People) are afraid to be like ‘oh… I’m going to be labeled as a snowflake,” Miller said. “These stereotypes, these words that people use,” increase polarization.

Miller said diseases have always been stigmatized by society because of the way in which they mark people, whether visibly or invisibly, and separate them from the community.

“So just the idea of others feeling like something that they have, whether it be a characteristic of them or they have a mental illness or physical deformity… or COVID now, they just fear the idea of being ‘othered,’” Miller said.

“Being stereotyped or labeled as being irresponsible and selfish,” can contribute to people not wanting to test or tell others they tested positive, Miller said.

That label is something OU sophomore Courtney Witte tried to avoid when she tested positive. While she alerted the people with whom she had been in contact so they could get tested, she tried not to broadcast her situation.

“I think the reason my experience (with people’s reaction to getting the virus) was positive is (I) didn’t tell a lot of people,” Witte said. “I was like, ‘no one needs to know, it’s not a big deal for me.’”

The Emergency Medical Services Authority, which serves Oklahoma City and Tulsa, has worked to ensure such stigma does not affect its first responders.

“It’s really important that our team members trust us to be transparent and honest,” said Adam Paluka, chief public affairs officer for EMSA in Tulsa.

“If they, number one, start to feel symptoms, or if they’ve been exposed to somebody who is symptomatic or who has tested positive, we’ve made it abundantly clear to them that they will not be punished if they are positive.”

The WHO describes this type of communication as important for fighting stigma. Word choices such as “infecting others” or “spreading the virus” can imply intentional transmission and assign blame.

That was something OU pre-nursing sophomore Callie Nester noticed to a small degree when she tested positive while living in a sorority house.

“(People’s reaction) was pretty much supportive, although there are people that are like ‘Oh she got it, so she must have done something or gone out somewhere to get it,” Nester said.

“But really at the time I was just going to the store with my mask on. I hadn’t done anything to really know where I had gotten it.”

EMSA has tried to follow the WHO’s advice on effective communication to continue to provide effective care to Oklahomans, Paluka said.

“We don’t want to (spend our time) pointing fingers, we want to spend our time lending a hand,” Paluka said. “That’s what we try to do day in and day out.”

Nestor said it is important to report testing positive because it helps others to track the coronavirus.

“I think there’s no shame in letting people know that you have (the coronavirus),” Nester said. “I think it’s important to report those (cases) and let people know that it’s real and it’s happening and there’s no need to hide it.”

Gaylord News is a Washington-based reporting project of the University of Oklahoma Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication.