WASHINGTON — U.S. House Rep. Markwayne Mullin (R-Okla.) on Thursday introduced a bipartisan bill alongside House and Senate members to expand a national mental health treatment program for which funding runs out March 31.

“We can’t afford to let that happen,” Mullin said.

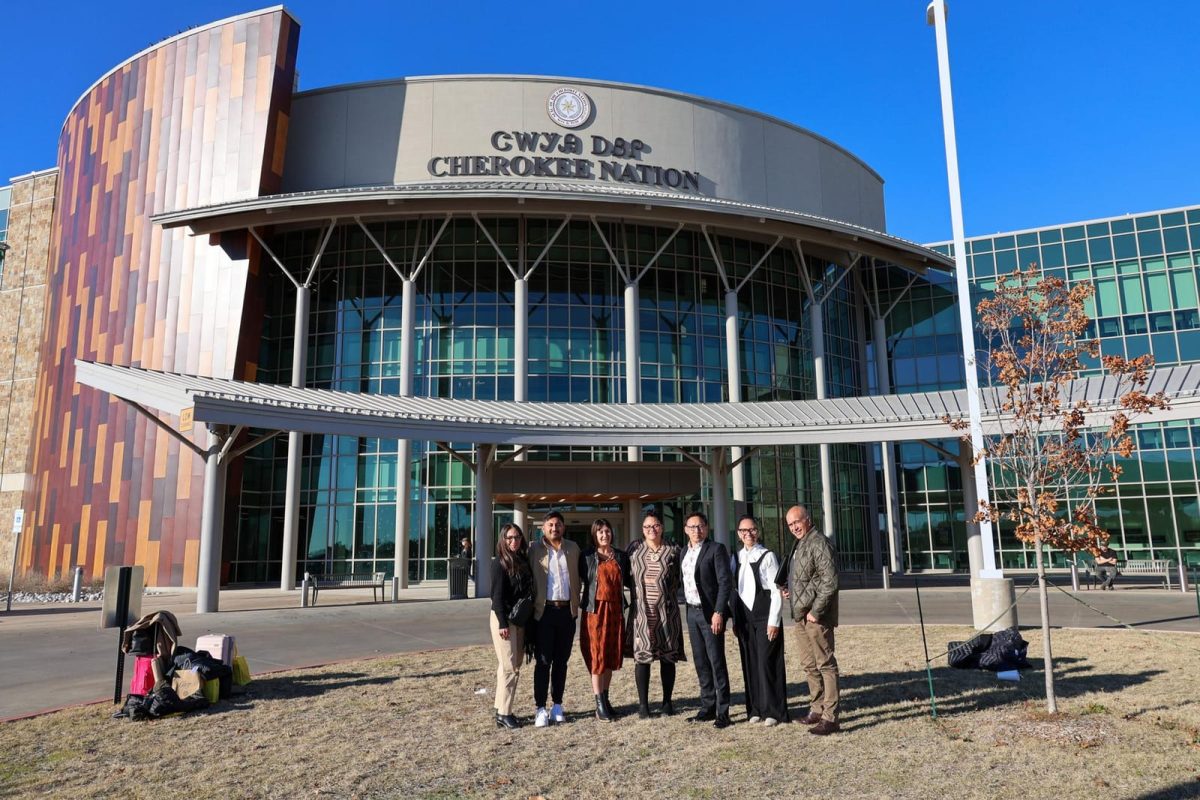

Oklahoma is one of eight states to participate in the pilot program, which established a Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic in Pryor, Oklahoma, through the 2014 Excellence in Mental Health and Addiction Treatment Act.

James Willyard, assistant police chief of the Pryor Police Department, said his department was “overwhelmed” by the mental health crisis before the Pryor clinic was established. Pryor is 45 miles northeast of Tulsa.

Officers spent up to several days waiting in emergency rooms with people experiencing a mental crisis and traveled up to an hour to the nearest treatment center, Willyard said. Now, it takes about 30 minutes for law enforcement to handle such cases.

It’s “changed the world for us,” Willyard said.

The proposed legislation would extend funding for the Oklahoma location for two years and create similar treatment centers in 11 additional states.

U.S. Sens. Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.), Roy Blunt (R-Mo.) and Rep. Doris Matsui (D-Calif.) stood with Mullin in backing the legislation.

“When we start talking about healthcare, there couldn’t be a bigger divide between Republicans and Democrats,” Mullin said. “So when we come together — it should get everybody’s attention.”

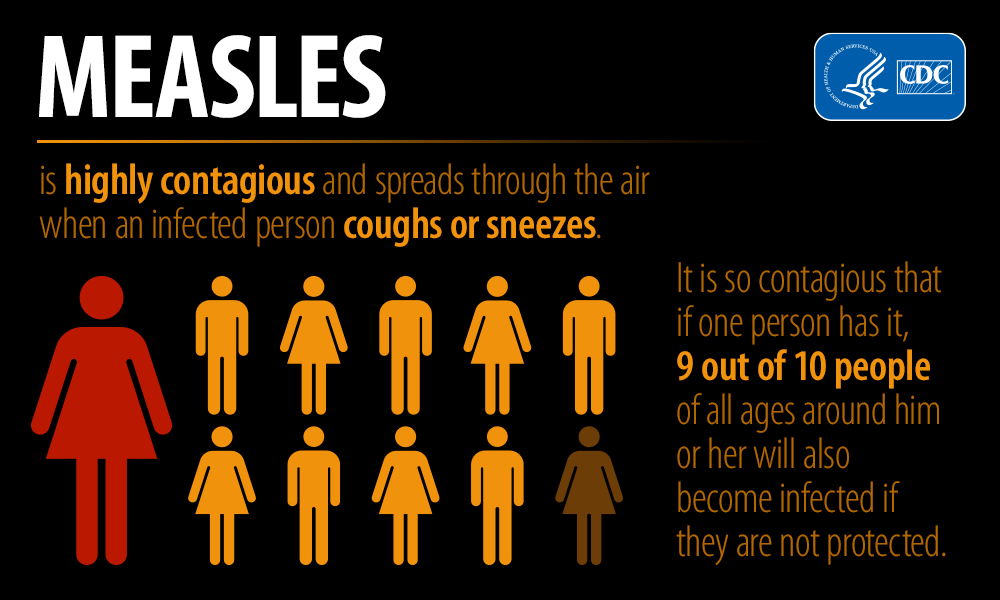

If funding for the behavioral health clinics is not extended, more than 3,000 staff could be laid off, more than 9,000 patients could lose their medication-assisted treatment and 77 percent of the clinics will have to re-establish waitlists, according to information distributed by the staffs.

The pilot clinics provide 24/7, year-around crisis services, outpatient mental health and substance abuse treatment services, immediate screenings and care coordinated through partnerships with emergency rooms, law enforcement and veterans groups, according to the staff information.

It’s a model that has proven results, experts say. The community clinics allow people to get treatment faster and closer to where they live, cuts down on incarceration rates and reduces the manpower required of law enforcement to handle the crisis.

“The data is ‘in,’” said Laura Heebner, executive vice president of the Compass Health Network. “The Excellence Act demonstration is a success.”

Mullin said he spoke with Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt about finding a state-level funding solution to bridge the gap before the program receives funding through the federal legislation, should it pass. But for now, the program’s future remains uncertain.

The possibility of the clinic losing funding could, among other things, mean strained resources for a police department that Willyard said is busier than ever — it’s “a scary thought,” he said.

“The opioid epidemic has hit all of us — it’s hit close to home, it’s hit immediately in my house,” Mullin said. “And it’s something that we should take very personally.”