Photojournalist documents Tulsans’ reactions to Trump rally

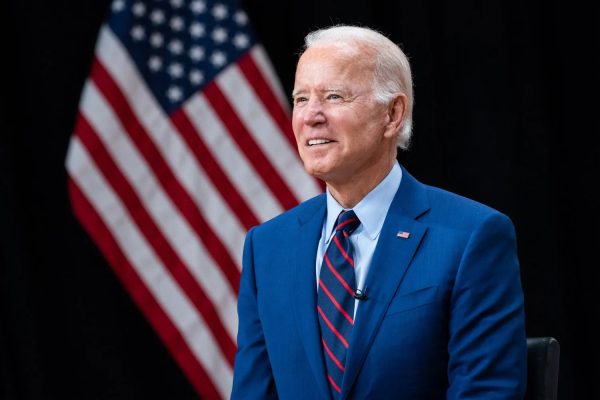

Oklahoma Eagle photojournalist C.J. Neal films a stand-up outside the BOK Center where President Trump is speaking. Photo by Wendy Weitzel/Gaylord News.

TULSA — C.J. Neal makes the two block walk from the newsroom to the businesses on Greenwood Avenue almost every day.

On his way, he likes to read the names of nearly 160 Black-owned businesses, which a century earlier had been looted and burned to the ground by white mobs, from a mural on the red brick walls of the buildings built in their likeness.

“People tried to come in and destroy a community,” he reflected, walking past on Saturday morning, nine hours before President Trump was scheduled to speak at the BOK Center. “They did damage it. People lost their lives. People lost property, but they didn’t chase the community that was here away.”

Then, he continued to the busy day of work ahead.

Neal is a photojournalist for the Sooner state’s oldest publishing Black-owned newspaper, the Oklahoma Eagle. His assignment for the day was complicated – get to the bottom of how Tulsans were feeling about President Trump’s rally.

Neal figured Greenwood was the easiest starting place.

As he knocked on the door of Black Wall Street Gallery, Ricco Wright, the gallery’s owner and a candidate for mayor of Tulsa, greeted Neal by name. The two discussed a sentiment that had been prevalent through the Greenwood community – the president’s timing was off.

Trump’s visit fell the day after Juneteenth, a holiday celebrating the June 19, 1865, emancipation of Texas slaves. Many in Tulsa’s Black community felt holding the rally this weekend would stoke tensions in a city trying to uncover and make amends for its history of racist massacre.

On May 31, 1921, a swarm of white people marched on Greenwood, firing indiscriminately at Black people, setting businesses and homes ablaze and dropping kerosene bombs from planes. After 48 hours of terror, the mob had leveled 36 blocks of the neighborhood once referred to as “Black Wall Street” and killed upwards of 300 people, the remains of whom have yet to be recovered.

Greenwood now marks a boundary in highly-segregated Tulsa between the majority white South and the majority Black North, where the implications of 1921 are still felt.

According to Human Rights Watch, 34 percent of Tulsa’s Black population live in poverty. Thirteen percent of the white Tulsans do.

“You know Tulsa’s ashamed of its past, and it’s always been afraid to be embarrassed, and that’s why there’s this current reckoning that’s happening,” Wright said. “Trump doesn’t help with any of it at all. Right now we don’t need people instigating something that is already in need of desperate reaction.”

It is a view Neal, a photojournalist for the Eagle and the founder of a civil rights, justice reform and women’s advocacy group, shares.

On his way to the BOK Center, Neal swings by the basement office he rents in the Reunion Building. The office serves as home base for his various organizations, including the Neal Center for Justice.

For Neal, it can often be difficult to find a balance between journalism and advocacy.

“There’s times I want to be an activist,” he said. “There’s times I want to put the camera down and pick up a sign, but there’s also times that I realized that if I do pick up that sign, I’m probably not going to have as much of an impact as I do standing behind the camera.”

“What I report on helps those people that are picking up that sign know the reason why they’re doing this and know the reason why they need to continue to do it until there’s change.”

Neal is committed to covering all sides of a given issue and holds that half-truths will never have the importance or weight of the whole truth. He believes that by uncovering whole truths for his community and for others, he has the ability to ensure that histories do not get covered up and lost to time.

Neal first learned about Greenwood’s tragedy in junior high. When he asked about it in history class the following Monday, his teacher had never heard of the event.

“The story was buried,” he said, “some of it out of fear, some of it just because people didn’t want to know the full truth.”

That’s the reason Jerry Goodwin, a candidate for the Tulsa City Council, said his grandfather got into the newspaper business in the 1930s by acquiring the Oklahoma Eagle. Goodwin’s father now is the Eagle’s publisher and his sister is the editor.

“They were only telling part of the American experience, part of the American dream,” he said.

“Now, there have been some openings (for Black voices) in majority media, but still, it’s not where it needs to be.”

A Pew Research Center Survey from 2018 found that 77 percent of newsroom employees across the United States were white. Only 7 percent were Black.

In recent weeks, amidst national discussions of systemic racism following the police killing of George Floyd, many journalists have called out the industry’s lack of diversity, including those at legacy newspapers like the New York Times and the Philadelphia Inquirer.

But until more diversity in newsrooms is commonplace, Goodwin says, Black newspapers like the Oklahoma Eagle will be a great value to their communities.

“We have been a voice for the voiceless community and those who have not had a voice,” he said. “My father continues to drill into me that as long as you continue to support the paper, people will continue to seek us out for our influence.”

is a journalism and political science senior at the University of Oklahoma, where she has written for the "Exiled to Indian Country" series and helped cover the U.S. Capital for Gaylord News.