Supreme Court affirms Muscogee (Creek) reservation status

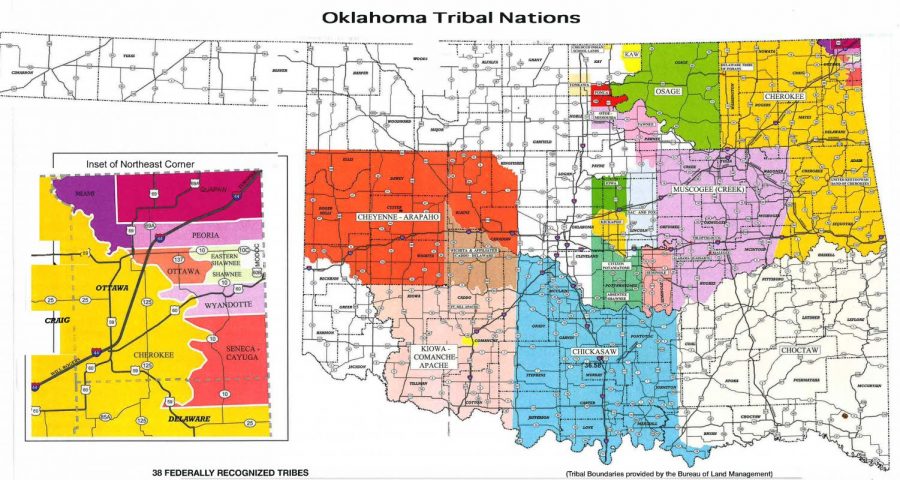

WASHINGTON — The ground shifted in Oklahoma shortly after 9 a.m. on Thursday when the Supreme Court ruled the eastern half of the state is still comprised of Native American reservations.

Suddenly, jurisdictional lines were rearranged: A member of an Oklahoma tribe can’t be tried in state court for major crimes committed in Indian Country.

In the 5-4 ruling on McGirt v. Oklahoma, the Court held that the status of the Muscogee (Creek) reservation had been questioned and diminished by Congress through history, but it had never been disestablished.

“If Congress wishes to withdraw its promises, it must say so,” Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote in the Court’s Opinion. “Unlawful acts, performed long enough and with sufficient vigor, are never enough to amend the law. To hold otherwise would be to elevate the most brazen and longstanding injustices over the law, both rewarding wrong and failing those in the right.

“Today we are asked whether the land these treaties promised remains an Indian reservation for the purposes of federal criminal law,” Gorsuch wrote. “Because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word.”

Most of Eastern Oklahoma is made up of lands given to the Cherokee, Chickasaws, Choctaws, Seminoles and Muscogee (Creek) nations, who are commonly known as the Five Tribes.

For the Muscogee (Creek) Nation based in Okmulgee about 100 miles east of Oklahoma City, the Court’s decision was a clear victory for their tribal sovereignty.

“Today’s decision will allow the Nation to honor our ancestors by maintaining our established sovereignty and territorial boundaries,” the tribe said in a statement.

But the tribe made clear that the decision wasn’t going to change the way laws are enforced on tribal land.

“We will continue to work with federal and state law enforcement agencies to ensure that public safety will be maintained throughout the territorial boundaries of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation.”

Tribal law experts said the ruling was unprecedented.

“Among Indian law lawyers, particularly those who represent tribes, there is a dark joke that the ‘real Indian canon’ is that the Indians always lose,” read a comment on SCOTUS Blog’s live coverage of Thursday’s opinions. “The reason is often the kinds of concerns about the consequences that this opinion rejects. That might mark the real sea of change that this opinion creates.”

Lindsay Robertson, Chickasaw Nation Endowed Chair in Native American Law and professor at the University of Oklahoma Law School, said: “You can sort of tell this when you read an Indian law opinion if it begins by telling you how many tribal citizens there are, or what the blood quantum percentage of a child or a parent is, these are things that have nothing to do with law, the court is being influenced by the present day reality on the ground and sort of extraneous stuff.”

“And this court went out of its way to say none of that matters, so this may be revolutionary,” he said

The case rose out of an appeal from Jimcy McGirt, who had been tried and convicted of raping and sodomizing a child in 1997. He argued that his convictions, which had been issued in state court, should be overturned because Oklahoma lacked jurisdiction in his case.

The crimes McGirt, a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, committed occurred within the historical boundaries of the tribe’s reservation.

Under the Major Crimes Act of 1885, serious crimes committed by or against enrolled members of Native American tribes are prosecuted in federal court and if convicted prisoners would be housed in a federal prison. Among the crimes are murder, rape, assult, robbery, kidnapping and other serious felonies.

The jurisdictional issues highlighted by McGirt’s case centered around the question of whether or not the United State’s long history of removals and broken treaties with the Muscogee (Creek) ever resulted in the dismantling of the tribe’s reservation.

The Supreme Court attempted to answer this question last year with the case Sharp v. Murphy, for which Gorsuch recused himself, having served on the 10th Circuit when they ruled on Murphy’s case.

The Court announced that they would hold an additional hearing on Sharp v. Murphy during this Court Term, presumably because they were deadlocked with four votes on each side. Instead, they decided to hear McGirt, a case for which they could have a full bench.

McGirt’s opponents expressed concerns that the decision could have consequences for the state’s criminal justice system.

“The State’s ability to prosecute serious crimes will be hobbled and decades of past convictions could well be thrown out,” Chief Justice John Roberts warned in a dissenting opinion.

However, both Oklahoma’s elected officials and the Muscogee (Creek) Nation have expressed a willingness to collaborate with each other and the federal law enforcement agencies to ensure that public safety will be maintained.

A joint press statement from the Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter and the Five Tribes, emphasized that the parties “have made substantial progress toward an agreement to present to Congress and the U.S. Department of Justice addressing and resolving any significant jurisdictional issues raised by the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma.”

Gaylord News reporter Breanna Mitchell contributed to this report.

Gaylord News is a reporting project of the University of Oklahoma Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication.

is a journalism and political science senior at the University of Oklahoma, where she has written for the "Exiled to Indian Country" series and helped cover the U.S. Capital for Gaylord News.