RezTok: Indigenous storytellers find stronger voice on popular platform

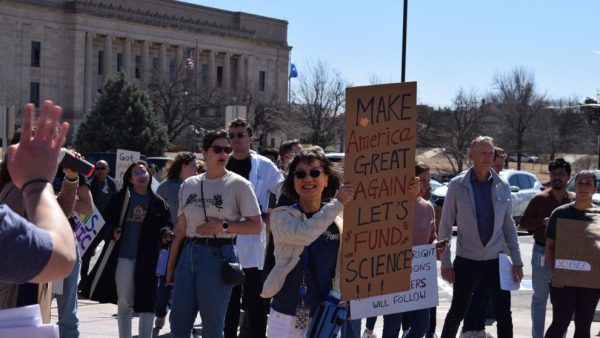

Like other Indigenous storytellers on RezTok, Yang often shares stories and personal histories that don’t show up in textbooks. (Photo by Jeff Rosenfield/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Native people across Turtle Island – an Indigenous name for North America – logged onto the video-sharing app for different reasons, but they stayed for the community, for the culture and to fulfill their sacred duty.

In recent months, TikTok has become wildly popular with Generation Z, especially given the extended time spent at home in the year since COVID-19 was declared a pandemic. Communities of all sorts have sprouted up on the app, and one in particular has been especially empowering and important to its members.

Native TikTok – also known as RezTok or Indigenous TikTok – has fostered important conversations around Native American issues and identities through a mixture of humor, education and the sharing of dancing, beadwork, poetry, storytelling and other artforms sacred to Indigenous people.

TikTok user @indigenousicon, a 19-year-old Diné woman whose preferred name is Yang, has built an audience of nearly 32,000 followers. She posts videos that represent Indigenous life, from traditional foods to dances in traditional Native clothes to raising awareness of racism against Native American people.

Yang said her use of TikTok as an Indigenous megaphone comes from a place of utilizing the technology and platforms at the fingertips of Native youth.

“Right now, there’s a lot of resources that can help us learn our culture,” she said. “And I think it’s interesting how we use these media outlets to spread that message of hope, resilience, love and most of all, I think it’s a healing component for our people.”

And this resilience, Yang said, comes in the face of the attempted genocide not just of of Indigenous people but their languages and traditions as well. As children and grandchildren of people who were put into assimilation boarding schools, she said, young Native people still grapples with the trauma.

“We cannot ‘just get over it’ – it’s something we have to heal from, something we have to get through as a community,” Yang said.

For Yang, that means using currently available resources and technology, including TikTok, to come together and invest in future generations by preserving Indigenous traditions and healing through community and camaraderie.

Beyond that, she said, creating Indigenous spaces like Native TikTok is important and more powerful than people may realize.

“When we hold those spaces, we reclaim our identity, we claim our cultures,” Yang said. “We’re still here to this day, we’re still living, we’re still practicing our traditions, we’re still maintaining our cultures, whether it be through video or whether it be through any kind of expression of healing.”

Yang sees hope in this.

“When I started to see other Indigenous kids representing their culture and turning their talents into art, into something beautiful — that gave me hope. It gave me hope that we’re still here.”

Brett Mooswa uses humor to further that quest for Indigenous hope, love and joy. He posts videos that poke fun at the Indigenous stereotypes perpetuated by centuries of racism and oppression. “Laughter is good medicine,” his TikTok bio reads, just below an impressive 381,000 followers and 5 million likes.

“I love doing takes on how the main community on social media thinks of us in a certain way,” said Mooswa, a Cree who lives in central Canada. “So I turn it into a cartoon in a sense just to show that we’re just normal people, doing the same thing as everybody else.”

This is a way, he said, to point out how outrageous and harmful the stereotypes and stigmas surrounding Native Americans are. Living on the Makwa Sahgaiehcan First Nation Reservation, Mooswa is no stranger to stereotypes and racism. When watching one of his videos, one can’t help but laugh at the absurdity of the caricature of Native people.

“They only like us in the 1800s,” he said. “When people think about us, they think about us dancing around a fire. It’s so primitive, and people say ‘OK, this is what’s going on, this is what I see in the movies, these guys are novelties.’”

And though a majority of his content is humorous, Mooswa said he likes to post more serious videos to highlight issues important to the Indigenous community. And in highlighting these issues with an air of seriousness, Mooswa finds support and community within what he calls the RezTok family.

“There’s a lot of people out there like me,” he said. “And I see that I’m not the only one that dealt with this. And hopefully it encourages them.”

But along with this community and this power to encourage people, Mooswa said, comes a responsibility to do the right thing and set a good example.

“I can’t be out there recklessly mocking my own way of life,” he said. “I have a responsibility to show people that they can be proud of who they are and be proud of their culture and where they came from.”

Nasheen Sleuth, a Diné mother and grandmother, started making TikToks just as the world locked down to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. Her videos range from raising awareness around Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women to encouraging Indigenous youth to teaching the differences between appreciation and appropriation when it comes to Native culture. In 2016, the Urban Indian Health Institute found 5,712 Indigenous women had been reported as missing or murdered throughout the course of the year, and activists have been calling for more attention to these deaths.

Sleuth said her journey to becoming a star of Native TikTok started with a video she posted explaining the Diné practice of going into the snow as a form of blessing and renewal.

“At that point, I had some other people that were Native and Diné and then other people from around the world saying that they do something similar,” Sleuth said. “So that was kind of what sparked this, but as time went by, there were other Native creators that were bringing up really sensitive and tough subjects.”

By acknowledging these issues, she said she found solidarity and community in Native TikTok, and she began speaking out on such issues herself.

As an aunt, a mother, grandmother, educator and mental health counselor, Sleuth considers it her duty to bring these issues to light and offer a safe space to not only her students, but Indigenous youth everywhere.

“I want (them) to know that I am someone that they can connect to, that it’s a good thing for them to share their voice, for them to share their experiences if they want to,” she said.

And Sleuth said she sees hope and opportunity for those young Natives she is trying to reach.

“They have the added advantage of having these rapid connections with other Native people, and they’re going to be able to use this to continue to share our stories, to continue to share our history and to learn from it,” she said.

Santana Rabang does just that. As someone who was disenrolled from the Nooksack Tribe (her father’s tribe in northwestern Washington) and therefore ineligible to enroll into her mother’s tribe, the Lummi Nation (just across Bellingham Bay from the Nooksack Tribe), Rabang uses TikTok to talk about the colonial roots of blood quantum laws and the damage they do to Indigenous people and their identities.

Blood quantum laws, originally put into place by the federal government, were used as a way to limit who could be adopted into a Native American tribe based on how much Native blood they had. Rabang, and many others, see this as a harmful way to judge “how Indian” someone is. She sees a better vetting process in ensuring that the person in question has sufficient tribal knowledge.

She has seen firsthand the harm done by blood quantum laws and works hard to decolonize this part of tribal government and policy.

“Did our ancestors identify through blood quantum?” Rabang asked, “or did they identify through their place-based knowledge and traditional ecological knowledge?”

Along with this fight against blood quantum, Rabang – who is Native, Mexican and Filipino – advocates for Native Americans who are multiracial. She wants to make sure that people like her don’t feel alienated or separated from their Native identity and culture.

“There are people out there who want to reconnect,” she said. “But there are these barriers of Natives that make them feel like they’re not welcome or that they don’t deserve to learn that side of themselves.”

Rabang said this is something she has seen even on Native TikTok. When she posted about her disenrollment from the Nooksack, some comments made her feel ashamed and outcast. All this did was fuel her mission and her fight against blood quantum.

“If we don’t take the time to challenge these societal norms that have been pushed on us through colonization, we are going to get booted off,” she said. “If I don’t fall in love with someone who is a full-blooded Native, my child is not going to be able to be enrolled, so it doesn’t just affect us, it affects our future children and our future grandchildren. It’s just sad.”

But she doesn’t want young multiracial Natives to feel discouraged by this systemic failure. She urges them to embrace who they are to the extent they’re comfortable with, and to fight the self-doubt that sometimes rises within multiracial people.

“You don’t need to ration your cultural identities out by percentages to make other people comfortable with your ambiguity,” she said. “You need to take the initiative yourself, to go out and learn your culture and do what you need to do to reconnect.”

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org.