Minh Nguyen, a Vietnamese man no more than 5 foot 5 inches tall, quietly stands in the middle of his restaurant in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, wiping down dirty tables. He calmly and carefully aligns each table in accordance to the one behind it. This type of order in his life was unthinkable 37 years ago, when Nguyen escaped from communist Vietnam along with his family and 43 other people.

He’s finally beginning to live the American dream in the twilight of his life operating Lee’s Sandwiches, a Vietnamese restaurant in the middle of Oklahoma City’s Asian district selling fast food sandwiches for $3.69 – a restaurant that opened in the heart of the Great Recession.

But adversity is something on which Nguyen was raised.

Nguyen grew up in southern Vietnam during the Vietnam War. When American military forces withdrew from Saigon on April 30, 1975, northern communist forces subjected any citizen who had official ties to the South, from military officers to religious leaders, to “re-education” camps. Nguyen’s father was in such a camp.

“My mom was able to bribe a prison guard so my dad could come home for one night,” Nguyen calmly said. “That’s the night my mom setup all the people with the boats who were ready to escape.”

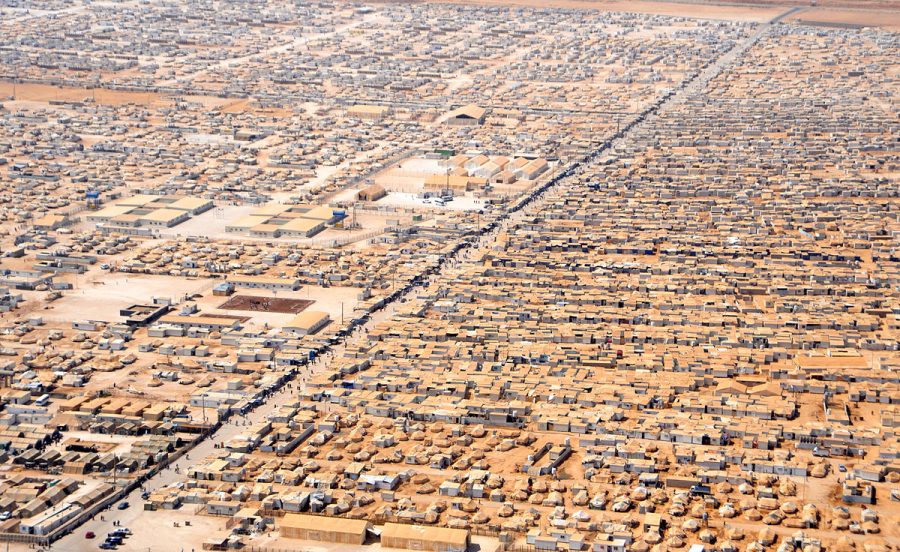

In the middle of the night, an 18-year-old Minh, his older sister and father, as well as 43 others set off on a cramped 39-foot-vessel with supplies for just five days and diesel fuel for even fewer. Minh’s mother reluctantly stayed behind, later to be brutally interrogated inside a re-education camp. The Nguyen family was only a small fraction of Vietnamese who sought refuge in neighboring countries. By the end of 1979, 25,000 people were escaping Vietnam per month, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency.

Nguyen met his wife when he arrived in California and they had two children. When his wife lost her job, she decided to move with their children back to her hometown in Oklahoma City. After working a number of years in California, Nguyen landed a job at Tinker Air Force Base repairing airplanes that allowed the family to be reunited.

Until 2008, Oklahoma lacked an inexpensive, quick-serve Vietnamese lunch and dinner joint. Nguyen and his wife noticed this culinary void and decided to invest almost all of their savings and properties into the business. Subsequent to taking out a small business loan, receiving equity-based credit on several properties including Nguyen’s mother-in-law’s house and $400,000 in credit card charges, Lee’s came to be on 30th Street and Classen Boulevard.

Nguyen’s wife has a love for cooking with traditional Vietnamese flavors, and used her knowledge to create the Lee’s Sandwiches menu. Nguyen said her recipes set their business apart from other Vietnamese restaurants in town because more people like the seasoning of the food Lee’s offers.

Although Nguyen and his family have persevered through situations almost unimaginable to the average American, their experiences have only reinforced their compassionate and caring approach to doing business, which Cathy Truong, a longtime employee at Lee’s, can confirm.

“Minh is great,” T

ruong said. “My mom is really sick, so I need flexible hours to leave whenever I want to. He’s allowed me to do that a lot throughout the years I’ve worked here.”

Last year, Nguyen hired his daughter, Jenny Nguyen, as Lee’s manager. Jenny doesn’t mind coming back to work in her parent’s shop given what her father has been through. “My parents needed someone to fill the spot, and I’m at that age where it’s kind of my turn,” Jenny said. “But I’ll give up 70 hours a week. [They] gave up their whole life.”

By hiring his daughter, Nguyen hopes to garner better relationships with his customers by promoting his restaurant on social media and digital platforms.

Truong said since Jenny came in as manager, the restaurant has become more modernized and pleasing to the customer. She said with the old manager, “we would have more angry customers than satisfied customers.” Now, she said they use kind gestures as a type of positive advertising so customers want to come back.

“I think my dad has done a great job in launching this business, keeping it alive and making it what it is today,” Jenny said, “but I think it’s now my turn to figure out what else we can do for my generation.”

Jenny puts less importance on setting themselves apart from other Vietnamese places around and more on the community aspect of the Asian District. “We are all so friendly with each other. We don’t even think of it as competition,” said Jenny, “We’re kind of all in this together.”

Since the 1970s, the Asian District in Oklahoma City has been a hub for the thousands of Vietnamese refugees who have moved to the area. Truong said she thinks Lee’s is the most diverse restaurant in the area because it reminds people of home.

As Nguyen finishes wiping tables, he humbly heads to the cash register to take orders. Although he believes his pace of life has slowed in Oklahoma City, he keeps his past close to him. He doesn’t forget how the northern Vietnamese tortured his mother to the point of disability after she helped his father escape brutal labor camps. Nor does he fail to remember how he went to three different schools for English every day while living in California on welfare. Or how Lee’s struggled financially for five years, until 2013. At Lee’s, nothing is taken for granted, and it shows in both food and family.

According to thevietnamwar.info, re-education camps were made to teach southern Vietnamese the ways of the new communist government with years of grueling labor. It is estimated that 165,000 Vietnamese people died while detained in re-education camps. Like Nguyen’s father, those who escaped hoped to attain refugee status and needed help finding a new life.