Anti-CRT law leads to little change in K-12 education

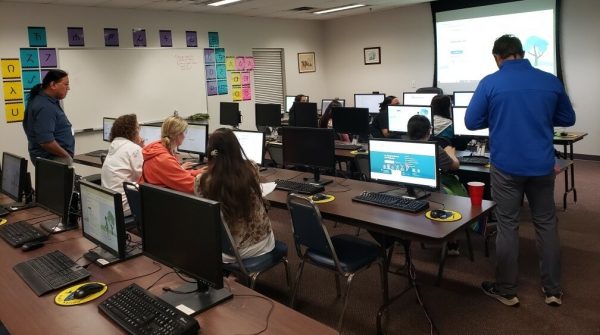

Educators initially struggled to determine how House Bill 1775 would impact classroom teaching. (Photo by CDC on Unsplash)

Educators across Oklahoma were left trying to figure out the premise and purpose of House Bill 1775, adopted in 2021, which prompted six pages of emergency rules connected to an academic field known as Critical Race Theory.

Anthony Crawford, who teaches English at Millwood Public Schools in northeast Oklahoma City, said confusion and uncertainty were the chief reactions of Oklahoma educators. He said the law has not brought about any curriculum revisions in his district.

“It really hasn’t changed,” Crawford said. “The thing about Oklahoman politicians is that they are not in our classrooms, they are not in our districts.”

What did change is the paperwork that the state’s 509 school districts must now complete attesting to the facts that they aren’t violating a state law about teaching a theory that’s discussed in graduate school.

Oklahoma was among 36 states that rushed to pass legislation banning the teaching of a theory that Fox News mentioned 1,300 times in a space of just four months a year ago.

“They like to claim it is a CRT bill, but we know that CRT does not exist in our P-12 school system,” said Katherine Bishop, president of the Oklahoma Education Association. CRT “is a master’s level course.”

“But what it does is it riles up their base,” she said.

CRT, according to Purdue University, attempts to demonstrate how racism continues to be a pervasive component of the dominant society, and why persistent racism denies people many of the constitutional freedoms promised in the governing documents of the United States.

The Oklahoma State Board of Education in its six pages of rules directed that no teacher or administrator can make part of any course eight “discriminatory principles” including that one race or sex is inherently superior to another race or sex, that an individual, by virtue of his or her race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.

The law has led to a lawsuit by the American Civil Liberties Union, ACLU of Oklahoma, the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, and pro bono counsel Schulte Roth & Zabel LLP on behalf of plaintiffs the Black Emergency Response Team (BERT); the University of Oklahoma Chapter of the American Association of University Professors (OU-AAUP); the Oklahoma State Conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP-OK); the American Indian Movement (AIM) Indian Territory on behalf of itself and its members who are public school students and teachers, a high school student, and two Oklahoma high school teachers.

“It seems like they are trying to rewrite history,” Crawford said. “It reminds me of the 1984 book by George Orwell, because in the book there was this portion of the book where they talked about people who rewrote history.”

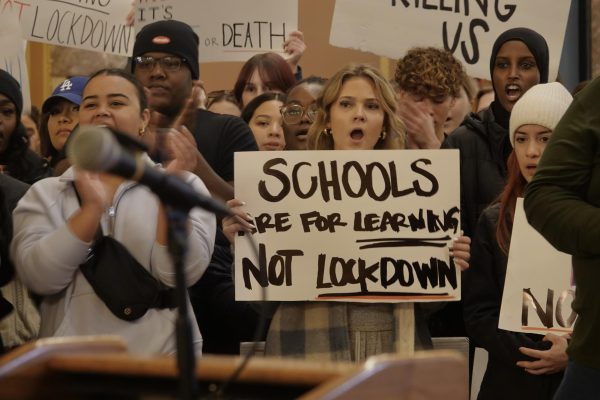

Megan Lambert, ACLU legal director, said laws like HB 1775 are detrimental to classroom teachers.

“It became clear that the combination of the extremely vague and convoluted language of the law, coupled with the racially charged language the legislators were using to discuss the law, meant that not only were teachers seeing official guidance restricting what they can say, teach and test in the classrooms, they were also out of fear self-censoring themselves,” Lambert said.

Problems arose in districts such as Edmond Public Schools, which faced controversy after ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ was removed from a reading list following passage of HB 1775. Some educators and ACLU members suspect it was a precautionary move based on the vague language of the law.

“I’d much rather have conversations about these sensitive topics, you know, while they’re still in my house, to read, or not to read them,” said Meredith Exline, a retired Edmond Public Schools board member. “I kind of explained to both my kids kind of what was hard for me to read in those books.”

Gaylord News is a reporting project of the University of Oklahoma Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication.